In the “getting to know” hot seat this month is a maker thoroughly committed to resisting the “IKEA-ification” of household furniture. Brian Clites is a fellow Anarchist Tool Chest user, acadmic turned professional furniture maker, and as as you would expect, thoroughly interesting chap.

As always it’s an honour to feature other makers on the blog. So let’s get to know… Brian.

1. You successfully defended your PhD dissertation last year. What was your PhD on, and how did you make the decision to move from academia to a furniture building career?

My recent doctorate from Northwestern University is in American Religious History. My dissertation, “Breaking the Silence: The Clergy Sexual Abuse Survivor Movement in Chicago, 1936 – 2011,” was an ethnographically-informed history of the way that this community has transformed their pain and suffering into an agenda of social and ecclesiological reforms. It was a very challenging topic to study for six years.

My decision to transition into furniture design was a mixture of pragmatism, ideology, luck, and an insatiable drive to create.

To be frank, I believe that the university system in the United States is broken. It is not broken merely because of its labor system. (In spite of being paid less than $100 per student per semester, I have actually loved teaching in adjunct and visiting lecturer capacities over the past five years.) It is broken because of the disjunct between what is taught and what is valued in our society. And because of academia’s inability to engage meaningfully in the crises of our time. In spite of its benevolent self-imagining, the American academy exacerbates more than ameliorates problems like inequality, bigotry, imperialism, and neoliberalism.

All of that being said, the same ideals that drove me to graduate school ten years ago have driven my transition from hobbyist to professional furniture building. Namely: the search for authenticity, meaning, integrity, and an anti-corporate lifestyle; my love for natural simplicity; and my lifelong goal of challenging – both physically and philosophically – the bare threads that hold together this vapid tapestry we call modernity.

It may not be true that teachers teach because they cannot do. But I build furniture because I cannot otherwise seem to live out the values that animate every fiber of my body.

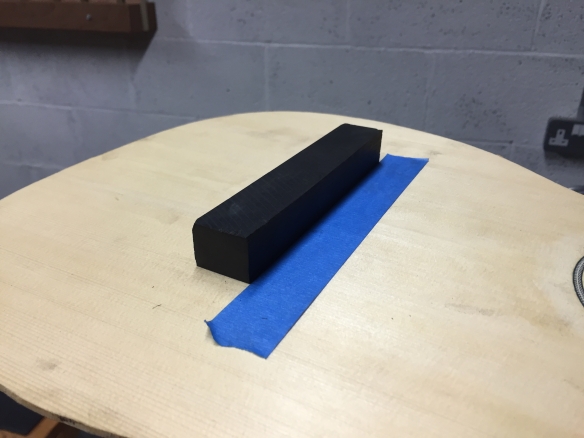

Tool Chest lifts by Brian

2. You’ve been building furniture professionally for just over 6 months now. How have you found those first 6 months?

As I was contemplating this life change last summer, I received a lot of helpful input from academics, friends, and family. However, the best advice I received was from Christopher Schwarz. As I recall, Chris’s words were: “One business model is to make a career out of your passions. To do whatever it is that you cannot keep yourself from doing. A ‘job’ that would make you happy whether or not someone pays you to do it. Find that path. And pour all of yourself into it. In my experience, the income will follow.”

On the ‘bad’ days – when I do not have any commission to speak of; when I’ve just ruined a drawer that I had already spent 14 hours on; or when my wife and I cannot pay the mortgage on time – on those days, Chris’s words ring particularly true. Because I am happier than I’ve ever been before, day in and day out, working with my hands.

A run of Brian’s windsor chairs

3. On your blog you’ve written about making a deliberate choice to use local saw mills, and how you’ve found that making that choice in turn has changed your understanding, and experience, of woodwork. Would you care to elaborate on that sentiment? How has the use of local saw mills changed your perspective?

I discovered another great mill just last week. The sense of awe and wonder I feel in such spaces is tough to describe. There is something fabulous about knowing the tree that a board came from, and knowing in turn the town in which that tree lived, the people who cut it down, and the millers who sawed and dried it.

Trees don’t talk to me. (Yet.) But the people who turn trees into boards have a lot of wisdom, a lot of knowledge, a lot of advice. And on the whole, I’ve found that they’re really nice folk. Men who are as interested in what I’ll do with the tree as I am in how they came to find, acquire, and process it.

Brian has a well-stocked Anarchist’s Tool Chest – I’m particularly envious of his collection of moulding planes!

4. You recently became involved in Lost Art Press. Tell me how that came about, and what your role at LAP involves.

I do not have any formal relationship with Lost Art Press. I was lucky enough to be in Chris’s last Anarchist’s Tool Chest class and, over drinks, we discussed the idea of a user forum, which he later invited me to help out with. Once the forum reached its beta stage, I stepped back. John and Chris do a great job with it. Most days, in fact, Chris replies personally to the new threads. I highly recommend the forum if you haven’t tried it yet, especially as a space for friendly conversations about the history and methods of hand tool woodworking.

5. In addition to building furniture you also clocked up a lot of time teaching last year. From your blog it looks like your teaching combines practical woodwork with a strong philosophical element. How do students respond to that mix, and how do you find those two elements compliment each other?

If money were not an issue, I would not teach philosophy. And I would not teach woodworking. Instead, I would (in my dreams) hold the first university position as “Professor of the Humanities With Your Hands.”

In the most socially-conscious of today’s classrooms, students are asked to think about the ethics of labor. But while all of them are consumers, very few young adults have (or will ever) produced anything tangible. This dissociation leads to a chasm that is breaking the social bonds of civilization.

Instead of having students read Walden Pond in a classroom, I want them to live in the woods for a week (or more). Instead of just reading about the Industrial Revolution, I want students to make a chest of drawers with their hands, then compare it to the Ikea crap in their dorm room.

In an era that defines ‘value’ solely as the lowest number of greenbacks, I seek to instill a different sense of that word in my students.

Value. Quality. Ethics. Aesthetics. These are not antithetical terms. And yet, in modern life, we so rarely can find them in the objects – not just the furniture, but also the clothing and especially the plastic devices – which literally occupy the most intimate spaces in our lives.

But to answer your question more succinctly: my students dig it. I don’t ask them to learn my values – just to recognize their hands as an extension of their mind (not some inferior, disassociated entity, as Plato and Augustine would have it, of which we should be ashamed).

Humans can think better with our hands than we can without them. And millions of western laborers do so every day. But we do not ‘value’ such symmetries of body and mind nearly as much as the abstract equations running Threadneedle and Wall Streets.

To make is to think. But the inverse, increasingly, does not hold true.