Dressing the front of the boot bench with my No3 smoother

I waited to clean up the dovetails on the boot bench until the very last stage before painting. The main reason for this is that I try to only clean up the exterior of a project once, so as to avoid removing any more material than I strictly need to. By waiting until the last possible minute I am also able to address any “workshop rash” to the exterior.

That moment of truth when you clean up a joint. This dado looks ok.

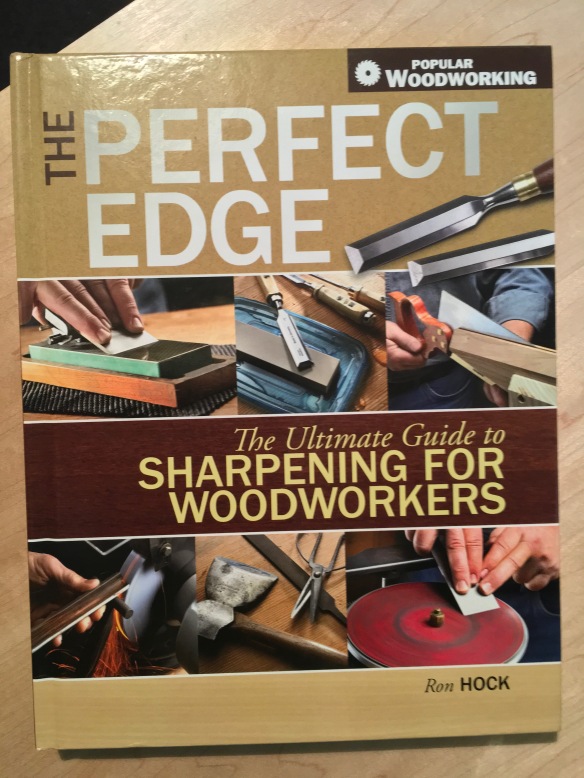

When cleaning up casework I try to approach the job in a methodical fashion, so that I only work on each face once, and to avoid denting or scratching a surface I’ve just cleaned up. This is all the more important given that workholding for a large-ish piece of furniture is different to flat boards. The most involved element of cleaning up the boot bench was the front, where all of the shelves intersect with the carcase, and need to be flushed up. I worked round the shelves in order using a freshly sharpened No3 smoothing plane and a No101 apron plane. Starting with the vertical divider, I flushed the ends up with the block plane, and then dressed the full length of the divider with the smoothing plane. Once the divider was flushed up, I then moved to the bottom shelf, and then each of the shorter shelves in turn, before lightly dressing the edges of the carcase. By moving around the elements in this order I was able to keep track of where I was, and also ensure that the casework is not planed out of true. When planing dados, skewing the plane to 45 degrees with a light cut as you work across the joint helps to avoid spelching or tearout on either component.

Drilling the pilot holes for more Roman nails. I wonder how many holes this drill has created over the years?

Once the front was looking good, I worked each end in turn before turning my attention to the top. The first task for the sides was to layout and drill pilot holes for the Roman nails which will pin the dados. The nails will be hammered in once the boot bench is painted, as I want the nail heads to be a decorative feature and not covered in paint. Five pilot holes per shelf were laid out with dividers, and drilled using a tapered drill bit in my grandfather’s egg beater drill. Next, each side was cleaned up with the No3 smoother taking light cuts until the pine was smoothly finished and the dovetails were flush. To work the ends, I placed the boot bench on top of a thick blanket to protect it from the floor, and braced it against the workbench. Some minor glue staining remains on the end grain of the dovetails – from my initial (highly unscientific) experiences Old Brown Glue seems to penetrate deeper than Titebond. As the boot bench will be painted this does not matter, and the joints were all clean with no glue left on the surface.

Trimming the dovetails flush

I trimmed the tails flush to the top with the block plane, and then smoothed the top until the surface was clear and free of tearout, standing the case on the floor (on top of a blanket) and bracing it against a bench leg. I’m pretty pleased with how these dovetails came out. The final touch was gently chamfering all four edges of the top, to avoid denting those delicate corners in use.

Clean dovetails, these look ok

I still need to complete the drawer, and apply finish to the whole piece. But the boot bench is almost finished, and should be in use by Christmas. In readiness for painting, I also applied blue tape to the inside edges of the casework and shelves, to avoid paint transfering to the interior. I have further strategies to address any paint that creeps under the tape, but you’ll have to wait until the next post for that.

Taping up the casework before painting