These dovetails (which Jim McConnell joked may have been cut with an axe) are rough in the extreme, but the drawer still moves smoothly after many decades in use.

The desk in our cottage. At some point in time someone had decided to fit this brass drawer pull, preventing the lock from being used. I wonder why they did not patch in the lock hole, or place the pull a little higher to completely hide the lock?

Making Things Work: Tales from a Cabinetmaker’s Life

” is essential reading for woodworkers and non-woodworkers alike, and her blog is full of thought provoking insights. So dear reader, please read on.

Nancy’s chest of drawers

A training in craft is a lesson in dissatisfaction. As craftspersons we are taught to internalize the message that we could, and should, always do better. Never mind the pots with minor defects in their glaze, the chairs whose turned finials are not a perfect match. However eagerly you long to exclaim “I made a chair!” you’re taught that these things are but means to an end: that great day when you will produce a Flawless Specimen, presumably the first of many in your career. For now, you must hold your head high as you hurl these personal indictments onto the bonfire.

***

One of my favorite pieces of furniture is a chest of drawers I bought at an antiques store in Reading (the English town, not its Pennsylvanian equivalent) circa 1984. At least a century old by now, it’s made of deal, a nondescript softwood, with knots and other characteristics usually considered defects. It was originally painted; traces of finish still linger in the cracks. By the time I came across it, a dealer had dipped it in methylene chloride stripper, which did the joints no favors. And yet it has held together over its three decades in my possession.

I love this chest of drawers, not least because it’s a mass of contradictions. It was made from defect-riddled paint-grade wood, but aside from the top, which is attached with nails, it was built with traditional joints cut by hand. Sliding dovetails hold the drawer rails in place. Stub tenons support the runners. The drawers themselves are dovetailed front and back; their bottoms, along with the cabinet’s back, are also solid. Altogether it’s a strange meeting of coarse and fine, at least by our own day’s standards.

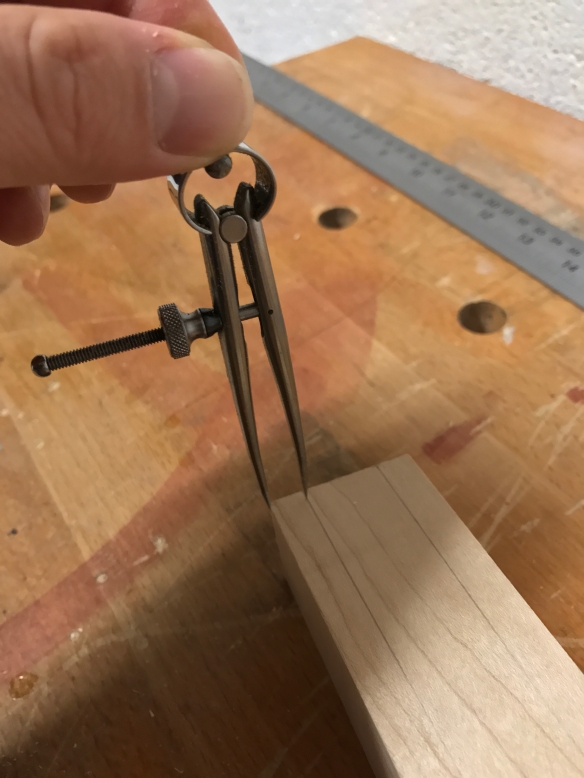

What endears the piece to me most is the dovetails’ imperfection. They taper to a fine point, a mere saw kerf wide–typically considered a mark of high craft. Yet the gauge lines were left in place. What’s more, many of the kerfs go well beyond those lines; and some of the joints have gaps. If I produced a set of dovetails similar to these, I would feel obliged to consider tossing the drawer into my version of a bonfire, the woodstove that heats our house.

Utility dovetails in the chest of drawers

These dovetails, which were clearly made by an accomplished craftsman intent on getting the job done, remind me that in the universe of making things, utility is no less worthy a goal than fine craft. Amidst the relentless drive to do better, it’s easy to lose sight of the grace that characterizes our very

ability to make things, however imperfectly, not to mention the blessings offered by even the most basic material artifacts. Yes, the things we make reflect who we are, at least to a degree; and who wants to be defined by radical imperfection? But there’s a conceit in being so wrapped up in the tightness and proportions of a joint that we lose sight of the bigger picture, which includes those who will use the things we make.

***

I often find I can’t look at a piece of my own work without focusing on the parts that should have been done better. Even as I tell myself it’s alright to be less than perfect, I feel a pang of self-loathing. Sometimes I get a chance to visit a customer’s home years after I’ve completed a job. I see a table or a set of built-in cabinetry serving its purpose in its intended setting. And I am able to appreciate my work separate from its reflection of its decidedly flawed maker. It’s a valuable corrective, revealing my self-flagellation as a form of vanity.

This is one of the wonders of making. In the end, it’s not about perfection. While craft entails much character-building struggle, it’s also a practice of learning to accept our failings and appreciate our role as makers who bring useful objects into the world.