Marking the rebates with the Veritas mortise gauge

I like dados for fitting shelves to casework – its an easy joint to cut, and especially when paired with cut nails, makes for very solid joint. The boarded bookcase calls for three pairs of dados to house the shelves, and a rebate for the top rail. Because I use dados quite frequently I keep thinking about picking up a 3/4″ HNT Gordon rebate plane, but cutting dados the way I describe in this post is quick (each dados takes less than 20 minutes) and fun, so a dedicated plane feels like an extravagance, no matter how pretty they are.

Setting a marking gauge from a chisel provides a quick and repeatable setting

I started by laying out the dados on both side pieces, ensuring that all layout was done from the reference edges. Once the shelf dados were layed out I placed the two sides against each other to check that each layout line was in precisely the same place on both pieces – this prevents layout errors and wonky shelves at a later date. The top rail is set 1/2″ in from the rear edge of the sides, and instead of using two marking gauges (one for each side of the rebate) I used the Veritas mortise gauge, with the two beams set to define the edges of the rebate at the appropriate distance from the edge of the side. The casework also features a kick underneath the lowest shelf. I don’t think Chris fixes this into a rebate when he builds the bookcase, but while I was in a grooving mood I decided to layout a rebate for this element too.

Deepening the layout lines

Once I was happy with the layout on the inner faces of the sides, I transfered the dados onto the front and rear edges so that the depth could be marked out. Where possible I like to set my marking gauges by reference to an object of known thickness rather than trying to line up the cutter with graduations on a ruler – this can be a component of casework, or in this instance a chisel of the right width. This reduces the opportunity for error, and makes for a repeatable setting.

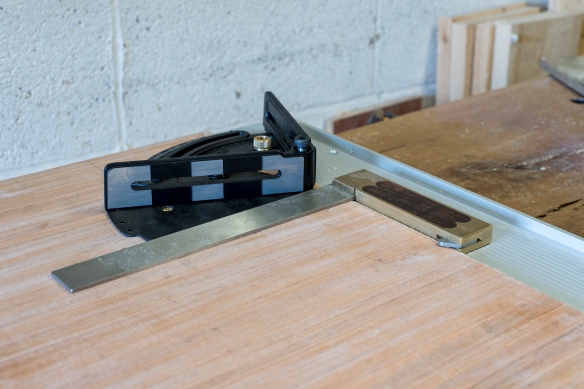

Preparing the first class cut

To cut the dados I use my Bad Axe Bayonet saw, filed hybrid. This saw has been specifically designed for cutting joinery, and the 14″ saw plate and fine kerf make it ideal for dados and other fine joinery. You can read a more detailed review here. Reaching straight for the saw might work, but you may also find the saw plate wandering across the workpiece and marring the surface, which is less than ideal. In the Anarchist’s Design Book, Chris describes using a batten and push stick as a guide for dead nuts straight dados, which is a nice approach. I go about it slightly differently, which shouldn’t be a surprise as there’s at least 17 different and effective ways to undertake any single woodwork operation.

Cutting the walls of the dado with the Bad Axe Bayonet

I use a typical approach for a “first class cut”. First I deepen the knife line with a gentle tap from a mallet on a wide chisel – I keep a 2″ butt chisel precisely for this sort of work and for paring tasks. With the line deepened, a long paring chisel can then cut a trench on the waste side of the line – the aim is to remove a small amount of waste with the layout line providing one wall of a “v” shaped trench. The trench guides the saw, keeping it running true. The first few strokes are gentle, and I keep two fingers of my off hand on the toe of the saw to prevent it from jumping out of the cut. Some lubrication on the saw plate helps too, particularly when the saw is cutting along the full width of the workpiece. A piece of blue tape on the saw plate helps to mark the full depth of the dado.

The majority of the waste can be removed with the chisel bevel-up

Once the saw is cutting at full depth along the length of the dado it’s time to chisel out the waste. Start with the bevel facing up – this is more aggressive and will knock out the waste quickly. It is vital to work from each end of the dado to prevent spelching at the ends. If you watch the saw kerfs it is possible to gauge by eye how much material needs to be removed. As you get closer to the bototm, switch to a bevel-down chisel orientation. Once I am close to the bottom I then move to the router plane to clean up. The router plane is not a bulk removal tool, so it really does help to have removed as much material as possible with a chisel. Placing blue tape either side of the dado helps to avoid marking the surface with the router plane.

Using the chisel bevel down is less aggressive, which is useful as you approach the bottom of the dado

I had limited shop time this weekend, so have a bit of work left to do on one side, but then the joinery will be cut and I can look at assembling the main structure of the bookcase.

Cleaning up the dado with the router plane