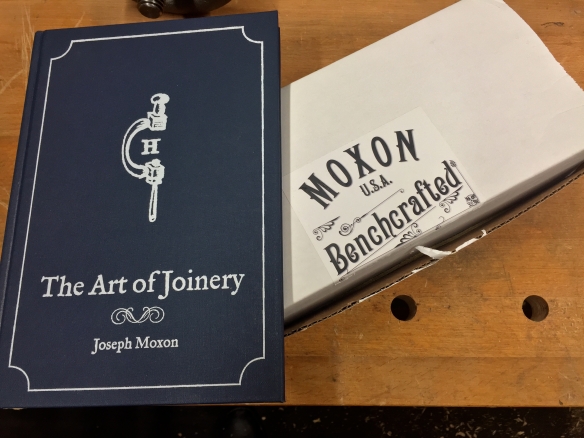

History was one of my first loves, specifically early modern English and North-European religious and political history. It’s what I studied for four years before I went to law school, and I still have my History PhD research proposal (and primary source material) saved on my laptop hard drive. One day I will attend to the siren call of the PhD. Which is an unnecessarily long winded way of saying that of my favourite titles published by Lost Art Press is Joseph Moxon’s 17th century text ‘The Art of Joinery‘. Moxon is mostly known for his description of the double-screw bench-top vise, which as a consequence is commonly referred to as a ‘Moxon vise’ (despite not being invented by Joseph). It seems like building a Moxon vise was pretty much an inevitability – a historic form of vise, which reduces the amount of bending I have to do at the bench (I’m 6ft2)? How could I resist? So recently I picked up the hardware from Benchcrafted (via Classic Hand Tools) and set to work.

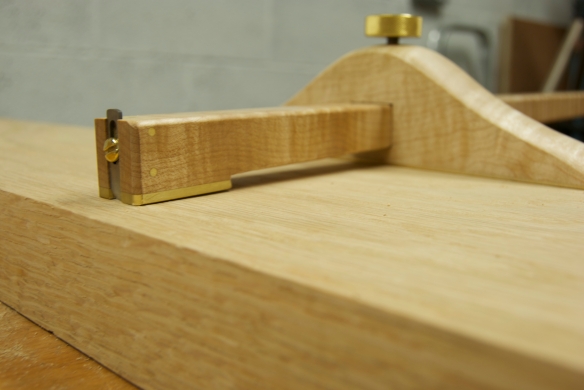

Marking the oak to width with my Hamilton Tool Works panel gauge

This also marked the Apprentice’s first trip to the timber yard, and she helped me pick out a 6 foot long board of 1 3/4″ thick, 6 1/2″ wide oak, perfect for a Moxon build. I’m keeping my Moxon pretty much in line with the Benchcrafted instructions, although I did decide to make the front chop the same depth as the fixed jaw. This is something of a trade off – the Benchcraft plans call for a front jaw which underhangs the fixed jaw to help align the vise with the edge of the benchtop, so as to increase clamping power. However this disparity in the lower edges of the jaws makes the vise less easy to store when not in use, and means that the vise can only ever be used at the edge of the bench. On balance, I’m happy to trade the benefits of a deeper front jaw for a more versatile (and easily stored) vise.

I cut the two jaws to width with my new Bad Axe mitre saw and vintage mitre box, which resulted in very clean and square ends right off the saw. At 6 1/2″ wide the jaws were over width by 1″, which is more than I’d care to plane off oak if I can help it. Instead, I clamped the jaws to the bench and hogged off most of the waste with my 116 year old Disston D8 rip saw using an over-hand grip. Although not a widely used technique, over-hand ripping is very efficient at removing waste very quickly, although it tends to leave a rougher finish than more delicate ripping on a saw bench. As a guide I lined up my layout lines for the final width of the jaws with the edge of my bench, so that the bench acted as a fence and stopped the saw crossing the line on either side of the workpiece. Ripping nearly 6′ of oak felt an awful lot like work, and while firing up the bandsaw would have probably been a faster way to remove the excess stock it would definitely have been less fun. The jaws were then taken down to final width with my No.8 jointer plane.

Having foresworn the ease of the bandsaw, I decided to stick with the handtool-only theme. Which mean that drilling the holes for the vise threads was an excellent opportunity to break out the 1920s era North Bros. brace and a 3/4″ Jennings pattern auger bit. I drilled the holes for the front jaw first, flipping the board over once the screw thread had started to emerge from the back of each hole. When it came to drilling out the fixed jaw, I clamped the two jaws together and used the holes in the front jaws as guides to ensure that I was drilling perfectly plumb and that the would be no minor variances between the two sets of holes which could foul the working of the vise.

The Benchcrafted hardware requires a bolt to be mortised into the inner face of the fixed jaw. This mortise can either be shaped precisely to fit the bolt, or simply an oversized round hole drilled with a large forstner bit. I didn’t have a large enough drill bit to hand, but in any event, I figured that if something was worth doing it was worth doing properly (even if no one would see the mortise). Which meant shaping the mortise to fit the bolt. With the vise rod passed through the fixed jaw, I threaded a bolt into position and marked the sides of the mortise round the bolt using a fine marking knife. If you are clever you can position the bolt so that all six of its sides run across the grain, which is what I did for the second mortise. If you have one or more sides of the bolt running along the grain (as I did on my first mortise, before I got clever) then extra care must be taken when chopping the mortise to avoid splitting the workpiece.

To start the mortise I defined the edges by placing a 1/2″ chisel into the marking knife kerf and giving a couple of sharp taps with a heavy mallet (I used the 24oz joiner’s mallet by Blue Spruce Toolworks). For mortises which have sides running along the grain, I chop all of the sides running across the grain first, and only then the sides which are with the grain. Chopping the sides in this order means that the sides running across the grain will act as a stop if the cuts with the grain start to split the workpiece. I then carefully pare away the fibres up to the edges defined by my chisel, using the same chisel in a bevel up position. Once a shallow mortise has been created it is possible to be much more agressive with the paring, turning the chisel bevel down and taking larger cuts to clear the material out swiftly. As I work my way round the mortise I chop the sides, followed by paring out the waste material, followed by another round of chopping then paring. Paring across the grain makes for very efficient waste removal, as wood is far weaker laterally (across the grain) than it it longitudinally (with the grain). Consequently it takes far less effort to pare even quite a deep mortise when working laterally than it would longitudinally, and I was able to chop these deep mortises (20.6mm, or 13/16″ in old money) in little over 15 minutes each.

The bottoms of the mortises were cleaned up with a small router plane to ensure that the bolts would be flush and square to the top, and the bolts fitted nice and snuggly with no rotation or slippage. Assembling the vise for the first time showed that the front jaw moved smoothly, and clamped with excellent pressure thanks to the heavy cast iron handwheels. Although it would be tempting to call the vise done at this point, there are a few finishing details I want to implement first, and I will write about these next time around.

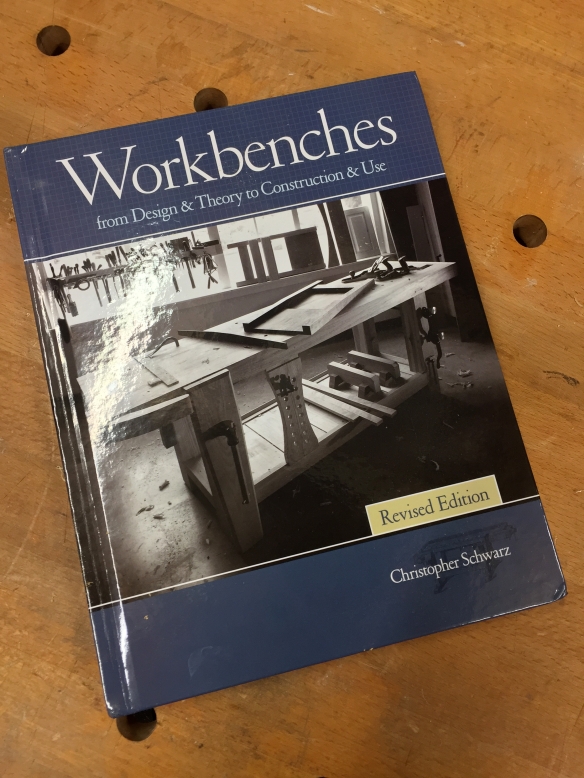

There is a rabbit hole down which most, if not all, woodworkers eventually disappear, regardless of what they make. And I now find myself teetering on the edge of this same rabbit hole. Let me explain.

There is a rabbit hole down which most, if not all, woodworkers eventually disappear, regardless of what they make. And I now find myself teetering on the edge of this same rabbit hole. Let me explain.