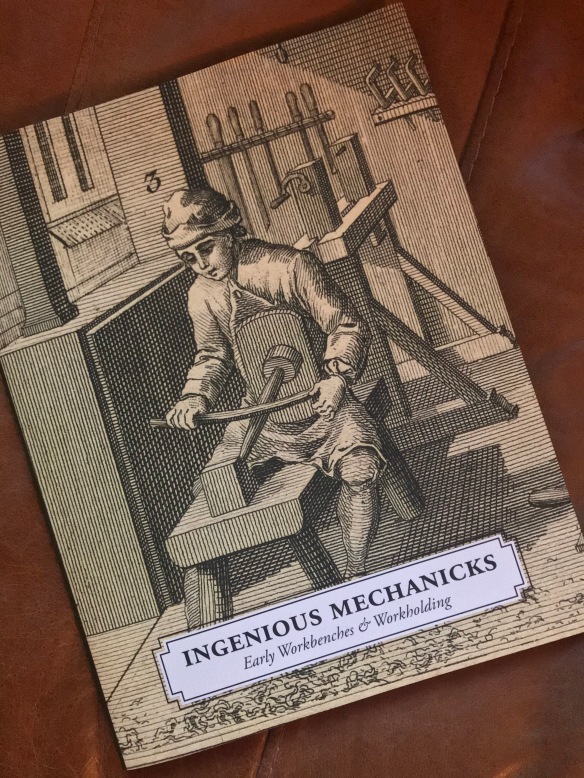

Aside from my round-up of favourite woodworking books earlier this year, book reviews are not really something I’ve done on the blog. But as soon as I finished reading Chris’ new book, Ingenious Mechanicks on holiday earlier this month, I knew that I was going to have to write about it here.

If somehow this book has passed you by, then it can briefly be summed up as an investigation into low workbenches and workholding solutions spanning a 2,000 year period from the Romans to 20th century Estonia, by way of China and South Ameria. In the book, Chris draws upon a vast body of history of art, written primary sources, not to mention the Saalburg bench – the oldest surviving workbench in the Western world (dating from 187 AD). The research is then rigorously tested by building four low bench designs and working at them to unlock techniques and working methods. So far so niche, you might think, but actually the information and lessons in this book have a wide application.

The book contains a useful guide to building (any type of) workbench with a thick slab top, which is a very welcome and helpful supplement to the Workbenches book. Next follows a detailed survey of the source material, and explanation as to how the research led Chris to build the benches as well as the simple appliances which increase their functionality. The production values of this book are high, as you’d expect from a Lost Art Press release, and the benefit is that the pictoral sources are reproduced with great clarity so that the reader is able to interrogate the images and reach their own conclusions about how artists have represented workbenches and woodworking. As I’ve written previously, history is one of my first loves, so this book was always likely to be like catnip for me. I wasn’t disappointed.

But putting aside my particular interests for a moment, as I was reading Ingenious Mechanicks I was struck by the recurring thought – this book is quite possibly the most important work Chris has published since the Anarchist’s Tool Chest. That’s a pretty bold statement, I know. But there are two reasons why I think this.

First is that Chris is presenting a way of working which is (for most people) entirely new – one which presents solutions for age old workholding problems, as well as new challenges. The vast majority of the way we work is from handed down knowledge – we learn from books, Youtube videos, or (heaven forbid) other woodworking humans in the same room as us. These are all healthy and invaluable ways of gathering and transmitting knowledge. But what I find exciting about Ingenious Mechanicks is that it offers something truly unique – the opportunity to experience a vibrant way of working for which not all the answers are known, and for which there is not a pre-existing corpus of knowledge on which to draw. Instead, the reader is presented with a chance to explore the benefits and limits of low workbenches and to report back from the frontline of woodwork research as they happen upon working methods and techniques. The only price of admission is to suspend pre-conceptions, and spend some time using unfamiliar workholding solutions.

Secondly, Chris has laid bare his workings and research methods. In doing so he provides the tools for others to research historic woodworking practices, and demonstrates how a rich seam of art history, archaeology, written primary sources, and an inquisitive disposition, can provide valuable insight into woodworking practices that are both historic and relevant today. Ingenious Mechanicks therefore becomes part woodworking book on pre-16th century workbenches, and part woodwork research methodology.

As I was reading the book I found myself asking questions about how familiar operations would translate to a low bench. Would wooden bodied planes respond differenty, or feel more comfortable, than metal bodied planes when processing stock? What sort of body position and posture would be necessary for sawing accurate dovetails? Would ow benches encourage the use of specific joinery techniques? There are few answers yet, and I know that there is really only one way to understand how these benches work. The oak for my slab-top Roubo bench is on order and should be here in the next couple of weeks. And now I am measuring up the workshop and trying to decide whether I should build one of these low benches too. And when all is said and done, persuading a reader to build one of these curious old benches goes to show just how effective Ingenious Mechanicks is.