The following is based on an article good friend Richard Wile and I wrote for issue 273 of Furniture & Cabinet Making. Although we hadn’t planned it this way, the article seems all the more timely given Auriou Tool Works current funding drive. Rasps are an integral part of the way Richard and I work, and we hope that this article will shed some light on their use and help identify which rasps might be most useful for readers to add to their toolchests.

A selection of the rasps and files in Richard’s toolchest

Rasps have traditionally been a mainstay of many handwork disciplines, including lutherie, chair making, shoe making, and stonemasonry. But they also make excellent additions to the furniture maker’s tool chest, opening up the possibilities of curves and transitions to work, as well as allowing for precise adjustments to be made to joinery.

The variety of rasp options available, including how coarse (or refined) the rasp cuts, together with the multitude of shapes and prices, and choosing between hand-stitched or machine cut rasps, mean that for the newcomer investing in a first rasp can be a daunting experience. This article attempts to help modern woodworkers introduce rasps to their woodworking hand tool arsenal, focusing on hand-stitched rasps, which are increasingly available from retailers in different price points (and which we both use to the exclusion of machine cut rasps), and explain how rasps can release your work from the tyranny of straight lines and square corners.

What is a rasp?

Rasps are shaping tools which excel at creating and refining curves, chamfers, and decorative detail. For the luthier, rasps can transform a block of the hardest figured wood into a graceful guitar neck, heel and headstock in no time. For the cabinetmaker, the rasp takes a bandsawn cabriole leg from rough to ready for sanding in a few minutes, refines the curve of a lamb’s tongue chamfer, or chamfers the feet of chairs and table legs.

While many rasps look like files with bigger teeth, they are in fact quite different. Firstly, the teeth of the very best rasps are let into the hardened steel by hand, through a process known as stitching. Each individual tooth is hammered in by a skilled craftsperson using a specialized tool called a “barleycorn pick”, a skill which takes years to perfect (see this profile on Michel Auriou or more discussion on this technique). Unsurprisingly, this handwork aspect is the greatest influence on quality, as well as cost. The slight imperfections and inconsistencies resulting from the hand-stitching process contribute to the rasps’ effectiveness; an attribute that machine made rasps are unable to replicate. A hand-stitched rasp is able to create a surface much smoother than their machine-made brethren, with far less chatter in use – even with difficult grained timber.

The near endless options

Similar to files, rasps are available in seemingly limitless shapes and sizes, including flat, round, semi-round, leaf-shaped, tapered, and tiny rifflers. A few simple guidelines will help the novice “rasper” to make an informed choice on where to start. The stitching of the rasp is the most important aspect to understand. Generally speaking, the higher the number, the greater the number of “stitches” per inch, and the finer the rasp. Individual makers use slightly different grading systems, but generally speaking a stitching of 4 to 8 is coarse, with 4 being extremely coarse for the most aggressive stock removal and 8 for more general rough shaping work. A medium stitching of 9-11 is the most versatile pattern for general woodworking, providing a controllable cut that requires minimal cleanup. The fine patterns range from 12-15 and provide the ideal configuration for final shaping or very detailed work. As a result, the high-grain rasps tend to be smaller than their coarser brothers, (generally 6-8” long).

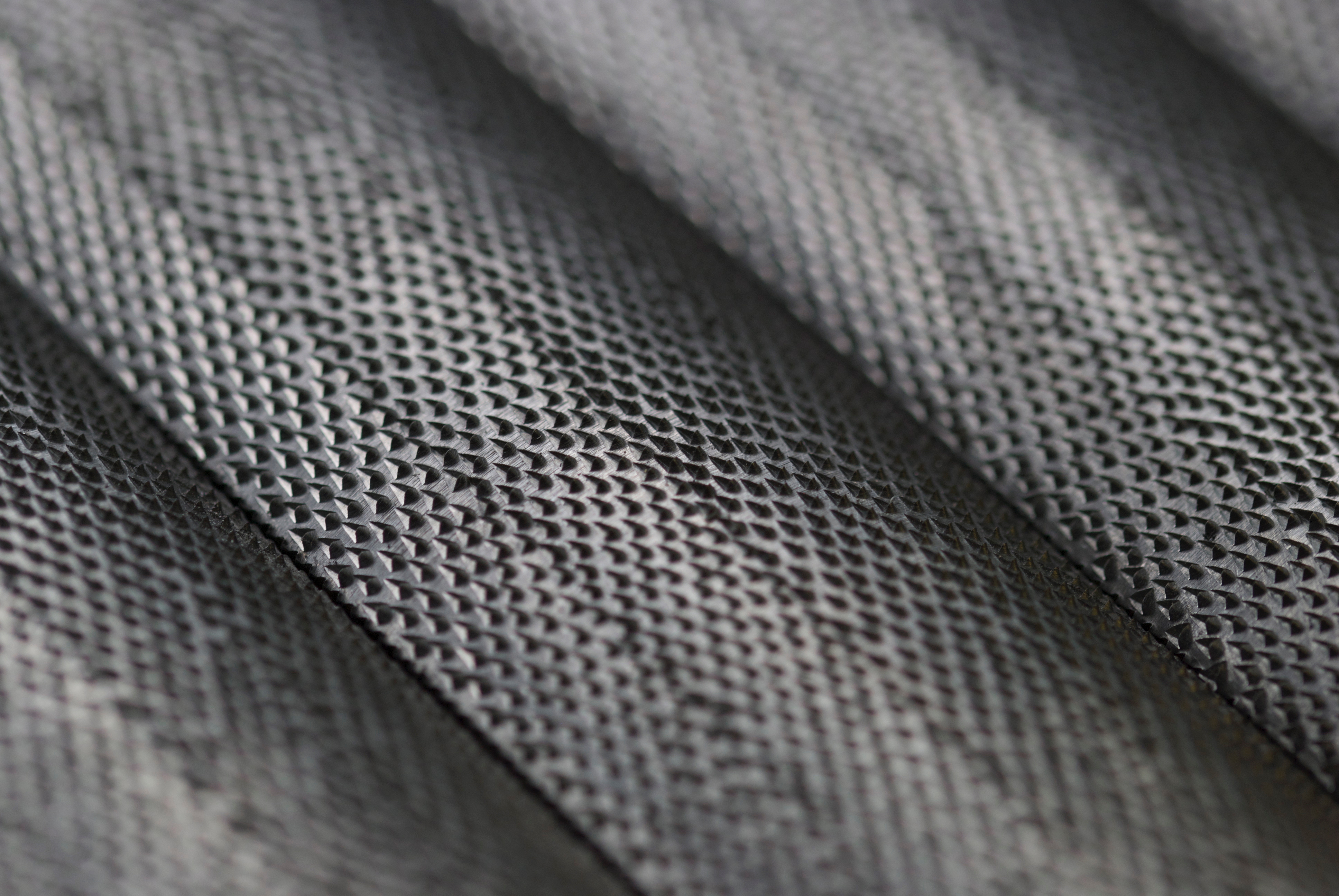

Handstitching rasps introduces minute variation to each tooth, resulting in a smoother surface on the workpiece, and less chatter in use.

Using a rasp.

The three categories of stitching roughly equates to the specific uses of the rasp; with coarse-grained raps suited to heavy stock removal or initial shaping tasks before introducing a finer rasp or moving to sandpaper. The medium-grained rasps are best for intermediate shaping and fine-grained rasps provide excellent tools for final refinement of the project.

Shaping a plane tote with a cabinet maker’s rasp

A rasp’s most powerful attribute is that it allows the user to shape in 3 dimensions – creating a rounded edge, or shaping a component, is done in one operation with no machine setup or jigs to slow you down. With the workpiece held in place, the rasp brings one’s creative abilities to the fore and allows a true organic expression of the woodworker’s skill to emerge.

Many uses for each type of rasp exist and rasps can enhance or even replace existing techniques. We have found that rasps do not seem to care about the hardness of the workpiece, and hogging away large quantities of material on the most stubborn of timbers can be carried out with ease. Wood can be rapidly formed to shape with a coarse rasp where bandsawing may be difficult or dangerous. Turners often use a coarse rasp to knock the corners or protrusions off a piece to reduce tearout on square or odd-shaped workpieces, and using the spindle lock on a mounted piece is an excellent way to get closer to round before turning on the lathe.

Small rasps give a fine finish and allow for very precise shaping

Medium-grained rasps are the most flexible, and a medium cabinetmakers rasp is a versatile tool if you only intend to buy one rasp. This type of rasp can perform a wide variety of shaping tasks and leaves a surface that can be cleaned up with abrasives if no other rasps are available.

The fine-grained rasp is for final refinement or very detailed work. With practise the woodworker can clean up a piece so that it requires no sanding; indeed these detail rasps can reach places sanding cannot, allowing smoothing of inside curves or complex shapes. These are also well suited to small work or small details in larger pieces; refining an edge detail with sandpaper is frustrating at times, while a rasp allows a controlled approach to get that final shape one is after.

Welsh stick chair maker Chris Williams shapes the arm of a chair with a coarse rasp

Regardless of how coarse a rasp is, the user’s cutting technique has a dramatic impact on the quality of cut. Much like carving, one must pay careful attention to grain direction to get the desired result. Working the rasp across the grain increases the roughness of the cut, removing material rapidly but increasing the risk of tearout. Following the grain produces the smoothest and cleanest cuts. Working along the grain can produce very smooth cuts that require little cleanup. Both can be effective techniques, depending upon the intended purpose. Heavy stock removal can be achieved by increasing how much you work across the grain.

Most hand-stitched rasps are handed, meaning they are designed to be used either right or left-handed. Using the rasp wrong-handed will result in a heavily scratched surface or with no wood removal at all. The general technique is to hold the rasp two handed, the dominant hand on the handle and the other holding the tip of the rasp. The smoothest cut is achieved by pushing the rasp away from the body along the grain of the piece; this direction is not always possible and practice will help to achieve the best result for the job.

Using a rasp is an extremely tactile skill, with the feedback through the hands giving more information about the quality of the cut than simply looking at the workpiece. Generally, the smoother the cut feels, the smoother the cut is, and if the rasp is jumping and chattering across the grain, the cut will be uneven and irregular. Remarkably smooth surfaces can be achieved with semi-rough rasps by using the right technique. Like most hand tool skills, best achieved with use and practise. There are few things more satisfying than feeling a rasp cleanly glide along an edge leaving behind a perfectly feathered and consistent facet for that important project.

Using Rasps for Joinery

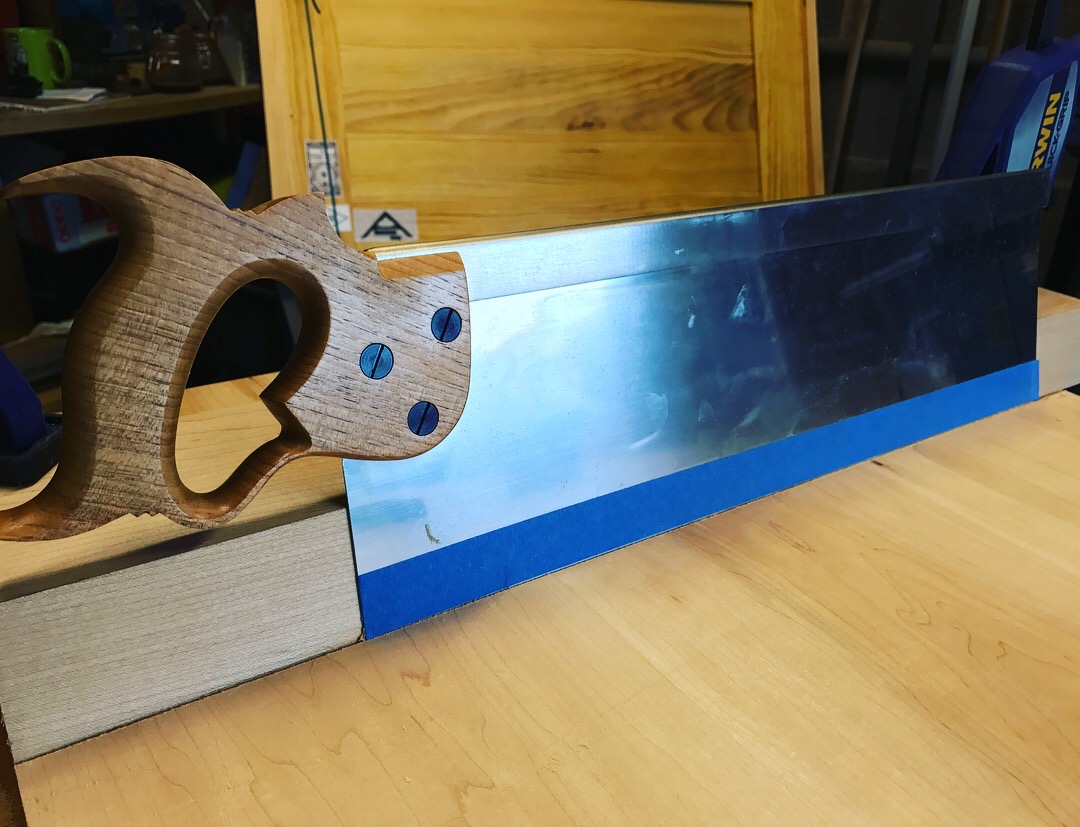

In many types of joinery, getting a good fit can involve fine-tuning the individual components. A medium or fine grained rasp can be an excellent choice for this type of work. Many joints involve flat surfaces, and the larger flat face of cabinetmaker’s rasp will register against the workpiece to stay in the correct plane. A through-mortise can be cleaned up or enlarged by gripping both ends of the rasp and aligning it with the face of the material to keep things square; sneaking up on the fit with light strokes. Tenon cheeks often need cleaning up to remove saw marks and to fine-tune the fit, once again the flat surface of the larger rasps is ideal to keep things square and in plane. Here the versatility of the rasp comes to the fore; simply by altering the force applied, one can easily control the amount of material removed for fine tuning or serious stock removal. For woodworkers who prefer to fit their tenons with a rasp, several makers offer a joinery rasp which is ideal for this application, and functions much like a planemaker’s float.

Large rasps are pefect for shaping tenons and other cylindrical features

Choosing your rasps

With rasps coming in so many shapes and grains, the conventional wisdom is to start with a 3-rasp set. The most versatile and useful rasp is the cabinetmaker’s rasp and is usually 12-13” long, with a flat surface and a semi-curved surface, and a medium grain finish. This rasp is perfect for general stock removal and leaves a surface similar to 80-grit sandpaper (depending on which grain you select) that is ready for final smoothing. The flat face provides a reference for smoothing and the size makes it much easier to use. If you buy only one rasp, this is the one to start with. Smaller than the cabinetmaker’s rasp, but with a similar overall shape, is the modeller’s rasp. Typically 8-10” long with a fine stitching, this rasp excels at final shaping and refining the surface left by a cabinetmaker’s rasp. The smaller size of the modeller’s rasp lets it get into small areas that may be difficult to sand and leaves a smooth surface requiring little or no clean-up. The third rasp in the typical starter kit is a medium grain rat tail rasp, for working tight radii, refining shapes, and widening holes for expansion joints. This rasp can also be used with light cuts to refine an edge, leaving a surface smooth enough to sand.

Rat tail and modeller’s rasps used to shape a miniature layout square

Properly cared for, high-quality hand-stitched rasps will provide many years of service and can open-up a whole new world of curves, flowing transitions, and precise fine-tuning of joints.