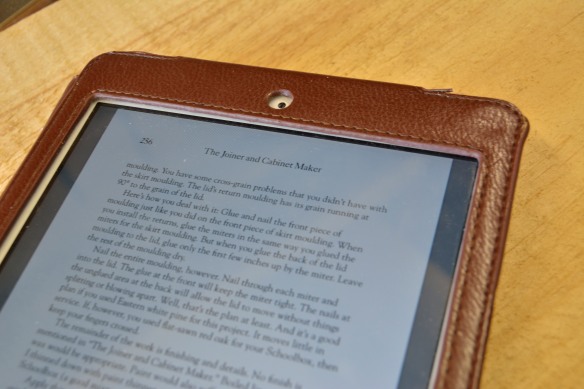

The following is adapted from an article I wrote for Furniture & Cabinet Making (published in issue 245).

My 16oz Lancashire pattern cross pein hammer by Black Bear Forge

Are you still dancing about architecture, or have you found a new way to describe and explain what you do in the workshop? Previously I questioned whether we as craftspeople need to develop a new vocabulary to clearly communicate what we make and how we make it, to spouses, prospective customers, and non-woodworkers, without relying on the crutch of technical and esoteric terminology.

It’s… Hammer Time?

Almost immediately upon hitting “send” for my last article I found myself in the unusual position of being a customer who needed to describe a specific set of requirements in a field where I didn’t have any technical knowledge and didn’t necessarily understand the specific terminology. This experience, while initially uncomfortable, forced me to think more carefully about the communication problems I’d just written about, and to formulate strategies to overcome them.

Because, you see, I wanted to commission a custom hammer from blacksmith John Switzer of Black Bear Forge. John’s work is nothing short of incredible, and this would be my third order from him, albeit the first custom tool I’ve asked him to make me. And because I know very little about blacksmithing, I had to find a way to set out very clearly what it was I wanted from this hammer – I knew that John would be able to make me exactly what I asked for, but the challenge was giving him a precise and clear brief so that what he made was really what I wanted. This commission would live or die by how well I (the customer) was able to communicate what I wanted. It also got me thinking about hammers far more than is strictly healthy.

Octagonal head, with domed face and a balance of decorative file work with “raw” metal still showing the signs of forging. Just what I asked for.

Funnelling the “Ill Communication”

When it came to describing my ideal hammer to John I took the approach of using an information funnel, describing each aspect of the tool starting with the most generic description and then drilling down into more of the detail, in order to build a comprehensive picture of the hammer. The generic description was for a 16oz hammer for driving 4d and 6d cut nails in casework. More specifically, I specified a Lancashire pattern cross-pein head, with a domed face to avoid “Frenching” the work, and for the head to be of square or octagonal cross section. I also wanted some decorative file work on the head, but balanced against plenty of unfinished metal so that I could see traces of where John had forged and worked the head. The handle was to be octagonal, as I prefer the handles of striking tools to tell me by touch which way the head is facing.

This gave a clear description of every aspect of the hammer for which I had specific ideas or requirements and I also provided an engraving from a pattern book showing the Lancashire pattern head I was looking for.

Campaign furniture is one of my favourite forms. But how would you describe this secretary using the information funnel?

So the information funnel works for hammers, but would I use it to discuss my lutherie with potential customers and lay people? Absolutely, and providing care is taken to avoid technical language, this is actually a very practical way of describing an object, or process, to a layperson. It sounds obvious really, but I think that we all have a tendency to reach straight for the technical terms (because who doesn’t like to wax lyrical about houndstooth dovetails, or the resultant angles of chair legs?). So, my three-point plan for communicating about what I do in the workshop now looks something like this:

- use the information funnel;

- avoid technical language; and

- use pictures to discuss and illustrate the more subjective, and ephemeral, aspects of furniture or guitars.

For conversations about lutherie, where possible I also use recordings which feature similar guitar tones to the one being discussed: either common touchstones that I share with the other party to the conversation, or where we don’t have similar music tastes encouraging them to recommend records that demonstrate the sort of sound they are describing.

Taking a dive into the metaphor pool

Although very practical, the information funnel is not the only way to avoid technical language when describing furniture. I recently discussed this problem with Raney Nelson of Daed Toolworks, who explained to me that he prefers to use a more impressionistic method of communication which he describes as “finding the metaphor pool that you both share, and then drawing on it”. So how does the metaphor pool work as a means of communicating about furniture?

This parlour guitar is braced to have a “clear, balanced, and warm” sound. But how would you use the metaphor pool to describe the same sound?

Raney suggested that the metaphor pool can work on several levels. With someone “whose background I don’t know, I can tell them that the desk (for instance) I have in mind is rough and ready, but with a sense of understatement, not in-your-face. And in the drawer details it incorporates some touches of really high refinement if you really pay attention, but without distracting from the strong utilitarianism and confidence of the piece in its function”. So far, so straightforward; but what I find really interesting about the metaphor pool method is the deeper level, where there is a common language pertaining to a field other than furniture or woodwork. Raney sets out his approach for this level of the metaphor pool where when he’s working “with someone who I know well and has a deep modern music lexicon, I can tell them it’s like Jon Spencer doing early Elvis Costello covers, but with a Jim Morrison affect. Much more Joey Ramone than Iggy, but also showing real refinement at the edges. Sort of a Norah Jones in the details, but without losing that Bonnie Raitt authenticity”.

So while the metaphor pool does nothing to describing the actual appearance of furniture, it can be a very effective method for describing the feel of a piece and its more ephemeral qualities, which Raney believes then predisposes the other person to understanding what he has made. So the hammer I ordered from Black Bear Forge would be precise where necessary, but still raw – like Jeff Buckley dueting with Janice Joplin, an honest working tool but with some real flair, like Bruce Springsteen covering Prince.

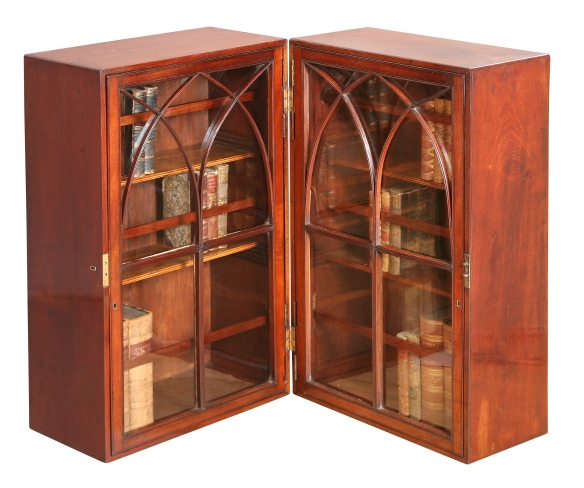

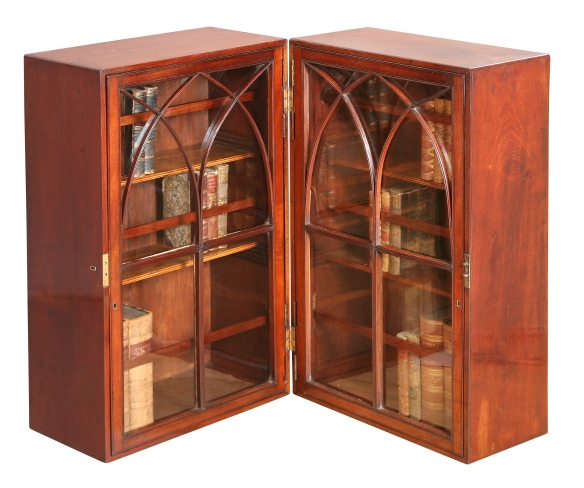

Would you use the information funnel or the metaphor pool to describe this campaign bookcase?

No need for a “Communication Breakdown”

Although the development of a universal, non-technical, vocabulary seems farfetched, I still believe that it is an ideal towards which we should strive. Without such a vocabulary, it is incumbent upon us as craftspeople to take the initiative when describing our crafts to non-woodworkers. There are many techniques for achieving clearer communication, from the precise information funnel to the more impressionistic metaphor pool, and the benefits of improved communication are an increased understanding within conversations with non-woodworkers, and ultimately making the woodcrafts more accessible.

And the hammer itself? Well as predicted, John captured everything I had asked for, and delivered a hammer which far exceeded my expectations. The balance is perfect and the hammer drives 4d and 6d cut nails almost effortlessly, even through difficult hardwoods. The handle is comfortable and the octagonal faces give a clear indication of the direction in which the head is pointed. The contrast between the mirror polish on the face, the decorative file work, and the “raw” unfinished elements of the head make for a wonderfully tactile tool, which proudly displays the processes which made the head. My only dilemma is how long I wait until I order an 8oz version for driving smaller nails. John’s work comes highly recommended.

The perfect balance of raw athenticity and decorative flair. Like Bruce Springsteen covering Prince?