The boot bench design uses a number of joinery techniques, which makes the sides quite a fun stage of the project. Through dovetails fix the top and sides together (tails on the sides, pins on the top), while the shelves are let into the sides by way of dados. Finally, the tongue and groove back boards are recessed into the sidesusing a stopped rabbet. Cutting the dovetails will wait until the top is prepared, as I don’t want to risk damaging the tails while working on the sides, but I decided to layout and cut the rest of the joinery for the sides as a short break from processing stock.

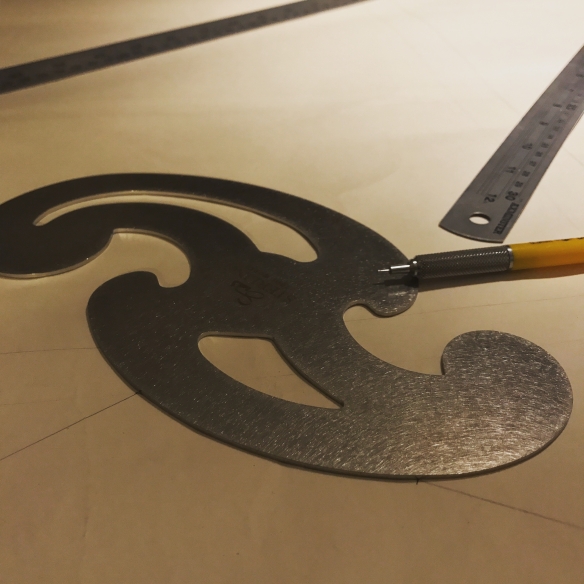

Precision tools for precision work – Vesper 10″ square, Blue Spruce making knife, and marking gauges by Glenn-Drake and Jeff Hamilton

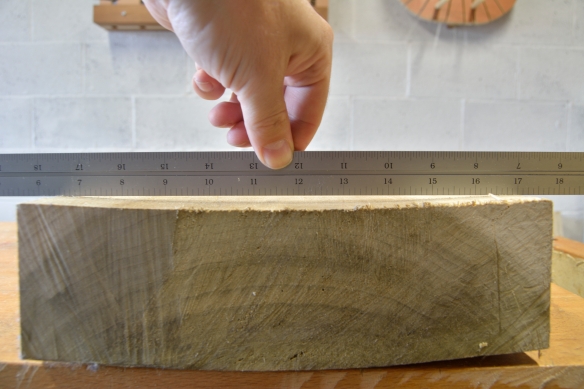

First I marked off the baseline for the dovetails, as this then gave me a datum line from which to measure the rest of the joinery. The shelves are 3/4″ thick, and let into 1/2″ deep dados. I have staggered the position of the shelves so that there is a distance of 5 1/4″ between the top two shelves (and between the top shelf and the baseline of the dovetails), and then 6 1/4″ between the third and fourth shelves. This spacing allows shoes to be placed on the top two shelves, and larger footware on the bottom two. The sides extend 3 1/4″ below the bottom of the fourth shelf, and will be carved into a cyma reversa foot detail. The stopped rabbet is 1/2″ by 1/4″ and extends from the dovetail baseline to the bottom edge of the lowest shelf.

With different dimensions needing to be marked off on different faces of the work I prefer to use multiple marking gauges, so that I can easily keep track of the measurements. All measurements were made on the reference edge of each side, extended across the workpiece using my Vesper 10″ square (which in my workshop is the final arbiter of squareness), and marked out using a Blue Spruce Toolworks small marking knife. I also coloured in the waste from each joint in pencil, just to avoid any confusion. Any time spent idiot proofing work is time well spent! To check that the joinery was correctly laid out I butted the reference edges of both sides together, and made sure that the layout lines matched for each joint (thanks to Charles Hayward for that tip!).

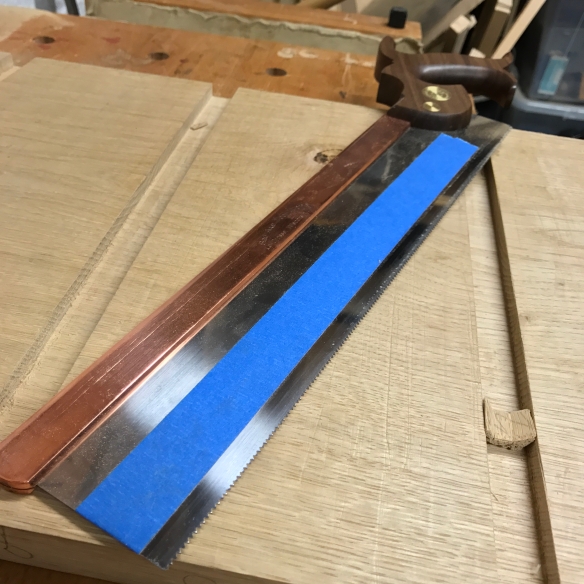

A high-tech depth stop

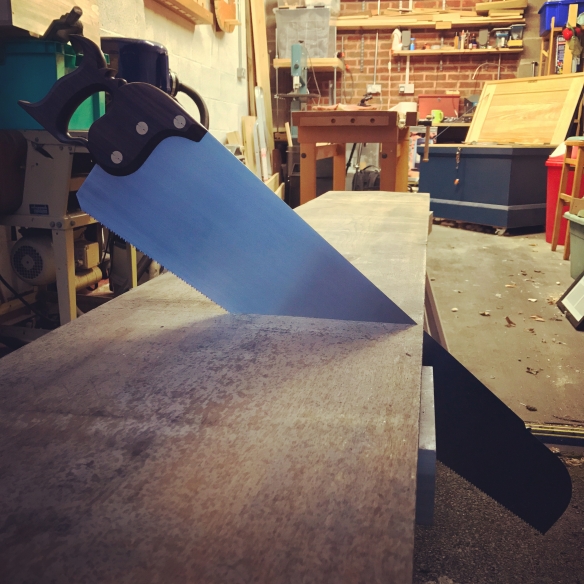

To cut the dados I deepend the knife lines with a broad (2″) butt chisel and mallet, and then pared a trench from the waste side down to the knife line – this trench guides the saw down the line and assists in maintaining a straight cut. It also ensures a nice clean surface for the joint. I cut a similar trench on the front edge of each dado down to the baseline. This project has been the first time I’ve used my new Bad Axe Bayonet in anger, and it really is the perfect crosscut saw for cutting joinery. To keep the saw in the cut initially I gently press a finger on the toe of the saw, which stops it jumping out of the trench. Once the kerf was established the Bayonet required no further assistance, and cut across the wide oak boards with ease. I’ll post a more detailed review soon. A piece of blue painter’s tape on the saw plate acted as a rudimentary depthstop (try as I might I couldn’t being myself to draw on the saw plate with a marker pen as Chris suggests in The Anarchist’s Design Book!).

Cutting a dado – gentle pressure at the toe of the saw with your off-hand keeps the saw plate in the cut

Once the shoulders of all four dadors were defined I knocked the waste out using a chisel and mallet – bevel up to hog out material quickly, and then bevel down as I got close to the base line. A couple of passes with the large router plane cleaned up the floor of the joint.

A large router plane is essential for cleaning up dado and rabbet joints

Once the dados were cut and cleaned I turned my attention to the stopped rabbet. Had a through rabbet been practical I would have reached for my skew rabbet plane and cut the joint in moments. However, a through rabbet would have resulted in a large gap through the dovetails, which is less than ideal. Instead, I made a series of deep relief cuts across the grain with a chisel, and before cleaning the bottom of the rabbet with the large router plane. Having already cut the dados to the rear edge of each side meant that the rabbet was effectively divided into a series of smaller sections, with access points at each end. This made cutting the rabbet easier, and this sequence of work is definitely beneficial.

The left-hand side, with dados and stopped rabbet all cut.

The sides are progressing nicely, and so the next task on my list is to carve the foot detail before I process the top and cut the remaining joinery.

Checking the rabbet for square with the Sterling Tool Works dovetail blade.