Right, I’m making up for departuring from the sequence of work from the text of Joiner and Cabinet Maker, and am back working alongside young Thomas. Which means that the next stage of the build is fitting the partition to hold Master John’s marbles and other precious trinkets.

The finished partition, all ready for Master John to fill with marbles and treasures.

The partition introduces some new skills to the story, including cutting a stopped dado to accept the side of the partition, and then friction fitting the side and bottom of the partition. This is my first dado, and I followed Chris’ directions in the text by using a guide block to ensure that the dados on each side of the box lined up correctly. To cut the dado I used the prototype Bad Axe Luthier’s Saw – this fine cross cut saw is perfect for precise furniture grade cuts, and in my time testing it I’ve found that I reach for it far more often than the specialist name would suggest. One particular benefit I’ve found is that the fine teeth make it a very easy saw to start on the corner of a work piece, where bigger teeth can catch until a kerf has been established.

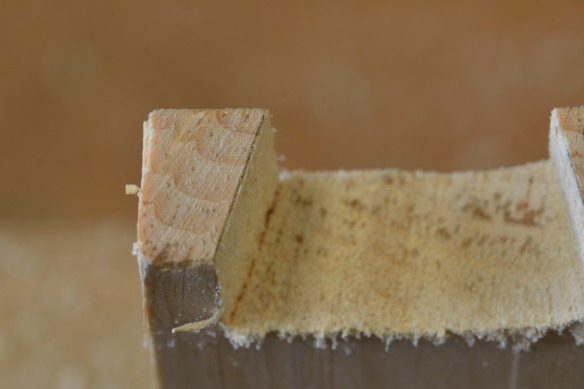

This isn’t sloppy work – the overcuts are hidden from view by the partition, and are fingerprints of handwork.

The waste was knocked out of the dados with a 1/2″ chisel and cleaned up with the small router plane, then the side was shot to length until it pushed cleanly into the dados. The bottom was glued to the side, and once the glue had cured I added 4d nails for extra holding power. Once fitted, the partition hides the overcuts at the bottom end of the dados but it pleases me to know that they are there as evidence of how I carried out that element of the build, and proof that the School Box has been built by hand. To support the base of the the partition I added 1/2″ thick cleats under each end, and these were fixed with 2d nails to the side of the carcase.

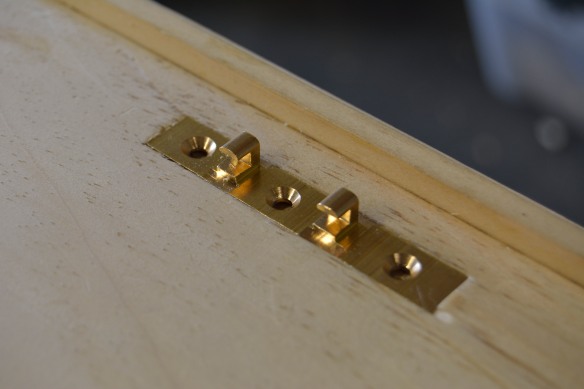

Once the partition was fitted I turned my attention to fitting the lock. When I fitted the lock to my Anarchist’s Tool Chest (a process I wrote about in detail previously) I used the same method as Thomas does in the Joiner and Cbinet Maker. Thomas’ approach is an efficient and accurate way to fit locks, so I followed his lead again here. There is no real trick for fitting locks, but accurately marking out the three mortises and cutting them in the right order, is essential for a fuss free experience. I used the small router plane to remove material for the top plate mortise, and a large router plane for the base plate and lock mechanism mortises.

A small router plane balances nicely on the edge of the box to cut the top plate mortise for the lock.

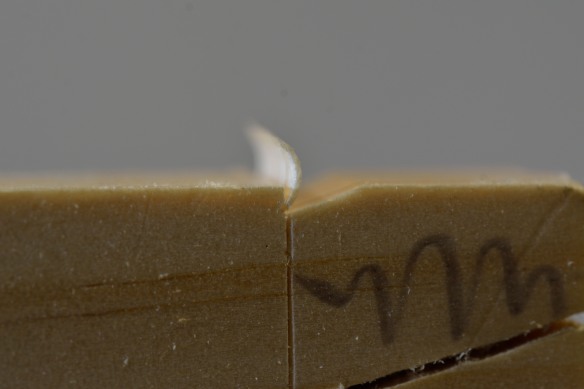

Cutting the keyhole is always a fun task, and I first drilled a hole to accept the key barrel. The escutcheon then slid over the drill bit and provided a template to sketch out the shape of the key hole, which was cut using a fine blade in a piercing saw before being cleaned up with a 13 grain rat tail rasp and needle files.

The escutcheon provides a handy template for marking out the keyhole shape.

Fitting the hasp is always the bit of installing a lock I find trickiest, mainly because lid moulding makes it impossible to sneak a small router plane in to bring the mortise to the correct depth, unless you balance the plane on the moulding (yes I have done this, but it’s not much fun). Next time I build a lidded box I will hold off installing any lid moulding until after the lock is fitted! That being said, it didn’t take too much work to get a good clean mortise into which the hasp would press fit, and the lock caught smoothly at the first turn of the key (which is always pleasing).

Cutting the keyhole to shape.

So all that is now left is carving the corners of the base moulding, and milk painting the completed School Box. Stay tuned for more coming soon!