It is inevitable that whenever you interview someone for a magazine column there is plenty of material that gets left on the cutting room floor. Fortunately there are no word limits on blog posts (although maybe there should be?) and so it is always possible to revisit the additional material in a later post. What follows is the full, unabridged, interview I conducted with wooden plane maker Matt Bickford for Issue 260 of Furniture & Cabinetmaking.

Plane maker Matt Bickford

- Alongside Larry Williams of Old Street Tools, and Philly Planes here in the UK, you are one of the first modern makers of wooden moulding planes, and hollows and rounds in particular. What prompted your interest in moulding planes?

There are many (and more) people out there that have included the versatility that these tools afford into their work. These tools offer what machinery simply cannot. Like the ability to use simple fore, try and smooth planes manages every width and length of stock available, the ability to manipulate simple moulding planes like hollows and rounds, which have always been what has allured me, offers the same idea of infinity. The internet, god bless it, has just brought us out of our basements, garages and sheds to share our discoveries together.

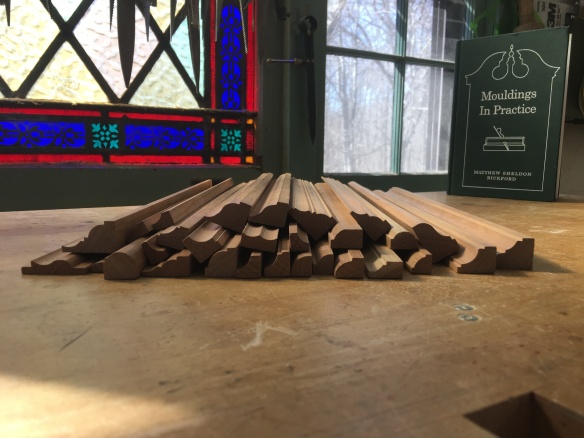

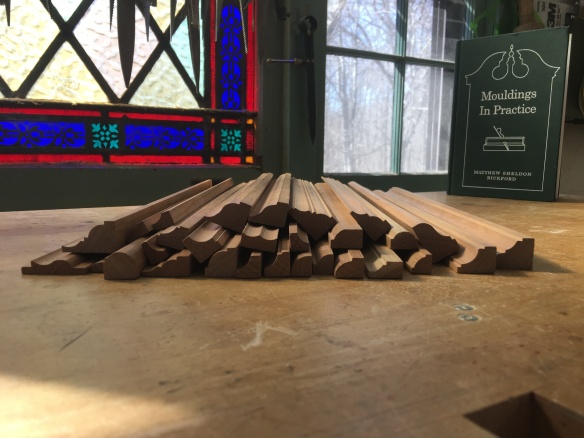

Moulding profiles, and a copy of “Moulding in Practice”

Along with Larry and Don, I may be one of first modern proponents of new planes and what properly made new planes afford the end user. If you purchase an old Stanley plane from a garage sale and immediately put it to wood you may conclude that old tools are substandard to the machinery and technology of today. In that same manner, if you pick up an old wooden plane and immediately put it to wood you will likely conclude the same. The jump in performance that can be achieved with tuning an old Stanley plane versus the exceptional quality of a new Lie-Nielsen plane can be achieved with wooden planes. Maybe the difference in knowledge and ability is due only to the amount of published literature or megabytes that have been dedicated to the two: metal planes get a lot of attention, wooden planes have not yet been funded the same. The same jump, or evolution, can be achieved. After all, likely the same issues are at stake. The differences are, I imagine, the perceived knowledge. I have certainly followed Larry’s lead in this respect.

Truth be told, Larry and his DVD introduced me to the idea of making my own planes. Prior to this video I had never considered making my own in the same fashion that, when I was twenty, I never considered making my own chair.

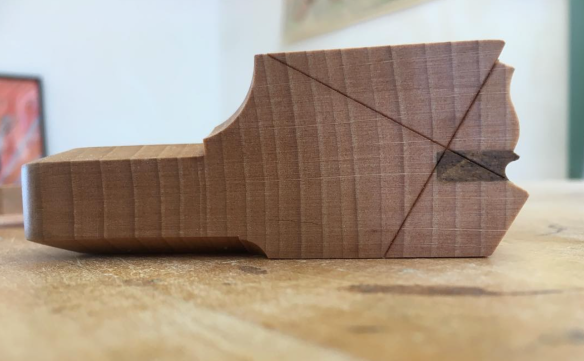

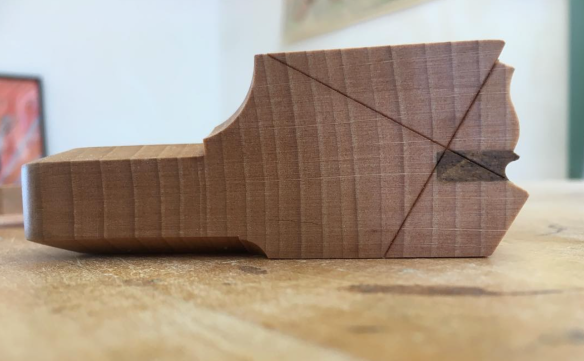

Complex moulding plane by Matt

I became aware of the absolute versatility that hollows and rounds afford through the internet, but I did not gain the ability of being able to use them through this same medium. Larry suggested that they could do anything. I then purchased an antique set and failed, failed and ultimately learned in my basement. Don McConnell’s DVD confirmed my technique. Ultimately, teaching people refined my procedure, of which I may be a modern proponent. Using this type of tool to create predictable and desirable results is not straight forward when holding the tool for the first time. The process, however, can be straight-forward. Hopefully my book helps in this regard.

So, in answer to your question, what prompted my interest in this type of tool is the idea of ‘infinity.’ With a basic set of hollows and rounds I am able to make every moulding profile that I may want, so long as the profile is straight (curved profiles are done with carving gouges and scrapers.) The projects that I choose are neither dictated nor decorated with the selection of router bits I may own, regardless of size. I can produce any moulding with the tools in my shop; I’m 20 minutes to 2 hours away from completing 8 feet of any profile.

Moulding plane Christmas tree decorations

- Your book for Lost Art Press advocated using a small set of hollows and rounds rather than complex moulders. How did you reach this approach? And can you explain the benefits of such an approach?

Let me start with this: complex, or dedicated, moulding planes have two major advantages over modern machinery. The first advantage they offer is that the sheared profile the plane creates does not need to be sanded, it removes the most tedious aspect. By not needing to sand you also do not risk the likelihood of dulling the sharp corners or drastic inflections that profiled planes encourage.

Additionally, antique complex moulding planes are not bastardized interpretations. Depending upon how far into this subject you may travel, know that today’s router bits are manufacturers’ interpretations of other interpretations of original mouldings, a progression of refined curves. There has been a lot that has been lost in the progression (read regression) of profiles. Complex moulding planes are, however, similar to router bits and shaper knives in one respect: they produce a single profile quite uniformly.

Pair of complex moulding planes

Hollows and rounds offer the idea of infinity. Any moulding profile is a series of flats, convex and concave curves. A set of hollows and rounds produces a varying number of progressing radii. Using this progression together allows an endless amount: the larger the set, the closer to infinity, everything.

In terms of a smaller set, most of our work does not include the entire range of moulding profiles. Those of us that make architectural crowns will likely not need the same set as those of us that make pieces that stand upon other pieces (i.e. mantle clocks, spice or bible boxes.) A smaller set of planes will likely afford the end user his necessary range. The necessary range, of course, may vary. My interests tend to fall in the even 2-10 range. (2s create a radius of 2/16ths of an inch, 10s create a 10/16th radius with the numbering system to which I ascribe.)

- To the beginner, hollows and rounds can be a little daunting. Can you explain your techniques for unlocking the versatility of these tools? What do you find inspiring about these tools?

Hollows and rounds have neither a fence nor a depth stop. It is the lack of these two features that allow the versatility that these tools both provide and encourage.

It will be difficult trying to explain the technique that I follow without a few dozen images. The process is straight-forward, but needs illustrations like my book. I started to illustrate this process in my blog and, ultimately, this led to my book.

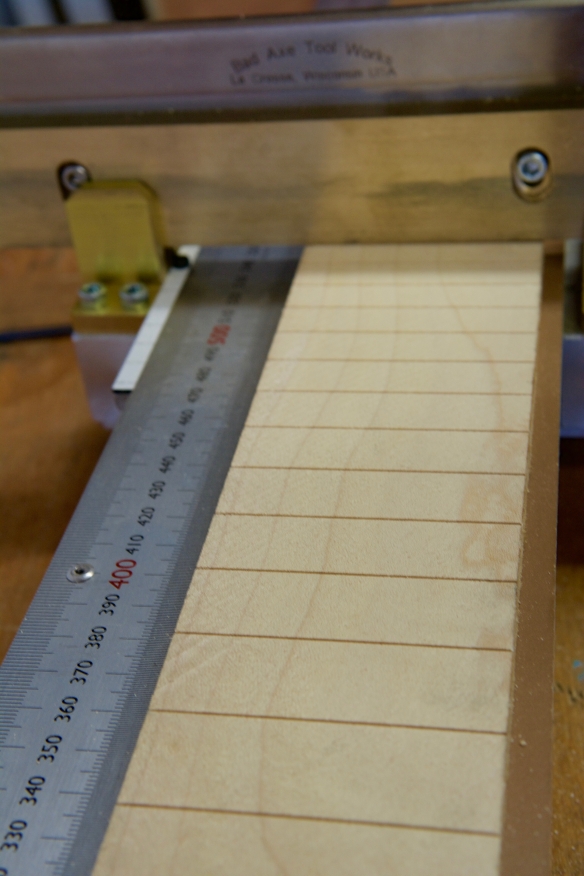

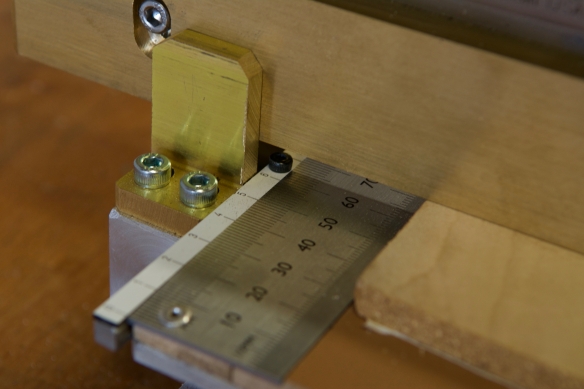

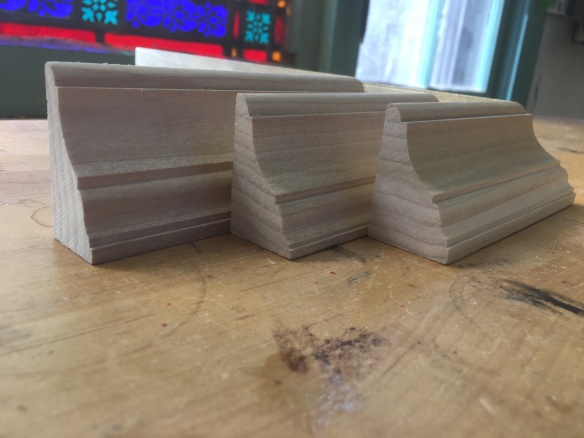

Matt’s method for using hollows and rounds starts with using rabbets and grooves to rough in the profile and steer the planes

In short, the real key to successfully using these tools is to give the plane two points to register upon instead of just one. As an example, trying to hold a hollow upon a corner at a uniform angle and uniform point upon the plane’s sole in order to create a convex profile is essentially impossible, but it is much easier than doing the same with a round to create a cove. Giving the plane two points to register upon instead of just one steers the plane, taking the place of the fence. It also gives a gauge for progress and replaces depth stop.

My blog and my book intends to illustrate a straight forward series of steps to follow to create something both desirable and repeatable.

A completed run of moulding

- It can be a big leap to go from furniture maker to tool maker. How did you make this leap? What prompted you to start making planes?

I was a hobby woodworker for many years. When I started making things out of wood I started copying grain direction, then proportions, curves, carving, etc. I had settled on a series of router bits to decorate my edges that I considered my own. This set was comprehensive and when I needed something larger than what I owned I pieced a few together to create the dimensions I needed. I was spending a lot of time copying all of these features, then I made a sacrifice with the moulding that I regretted prior to making it, but I had settled upon my set and pushed forward.

Carved leg by Matt

Finally, I went in search of other options. I was tired of making sacrifices and, through Larry’s writing, became aware of another option. I purchased an antique set of planes that, regardless of how long I spent with them, disappointed. When Larry came out with his DVD I decided to make my own. The first planes that I made for myself worked better than any antique that I tuned and also gave me the knowledge to tune any antique that I purchased.

How did I make this leap into making planes? It kind of just happened.

- What is the element of plane making that you find most satisfying?

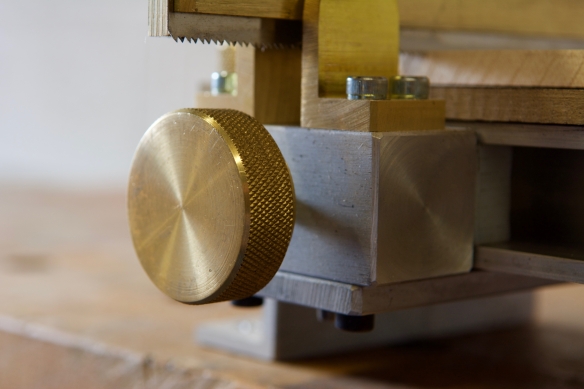

I technically make 18th-century British reproduction planes. These planes represent the point where all of the technology was in the tool but none of the machining process had yet been taken out. These tools, despite the fact that they are a piece of steel and two pieces of wood, represent a significant amount of technology.

A pair of snipes bill planes by Matt

I am still fascinated by the amount of technology included in these seemingly simple tools. The final product that I create will never change and I am satisfied by the small changes I make in an effort to stream-line the process.

Every plane that I make (and I have made thousands) I still consider the best that I have ever made. I am fascinated by what the planes can do, how the planes perform, and the possibilities that these tools encourage.

- You’re known as a plane maker, and for the book you wrote for Lost Art Press. But you are also a furniture maker. What sort of furniture do you build? Are there specific styles which you particularly enjoy building?

I make furniture as a hobby, which is difficult once you are working wood throughout the day. My friends, who are also professional woodworkers, and I started a woodworkers’ guild. We meet one night each week at my friend’s shop where we work on projects for ourselves. This encourages us to continue making things we want to make and to push our own limits.

Table by Matt

I have always been attracted to Queen Anne and Chippendale furniture. My parents had reproduced examples throughout our house growing up and I like the idea of potentially making things as good or better. I tend to like carving. The pieces that I make must have carving or I will not be interested. Once I am done with the carving I will not likely finish it (see the corner of unupholstered furniture in my basement). The mouldings and moulding planes are just a supplement. It’s kind of silly to make a sacrifice in the piece’s appearance in low-light when spending so much time casting shadows with carving in full light.

A ball and claw foot Matt is carving

- You’ve been posting photos of really interesting moulding runs to Instagram recently. Where do you get your inspiration for moulding profiles?

I like to think that I am good at recreating some things. My imagination with the ‘new’ has not yet been set free because I am still fascinated with recreating the old. Most of the things that I have made have, to varying degrees, been recreations. I’m still in love with the idea that I can make what others already have.

- If you had one tip for aspiring tool makers, what would it be?

My advice is for aspiring woodworkers, not necessarily tool makers: see what has been done, consider what has been done, try to make it. You may have no desire to put pad, trifold, or ball and claw feet in your living room; you may not want turned, cabriole or ogee bracket feet; you may not want waist, base or crown moulding, but seeing and considering how each of these treatments have been included into others work will give you an idea and an inspiration into your own work. Look at what has been done throughout the centuries and consider the conclusions of the past, even if you do not include it in your own work. A lot of inspiration is out there, and it is all relevant. This same logic applies to making tools.

“All inspiration is relevant”

- For woodworkers just investigating moulding planes for the first time, what limited set would you recommend?

A simple set of hollows and rounds is ideal. These planes are easy to rehabilitate, sharpen, maintain and, despite the ambiguity, to use. Hollows and rounds are extremely versatile and encouraging. Dedicated planes are fun to use but they are one-trick-ponies. Two pairs of hollows and rounds give the end user the ability to make scores of moulding profiles, the ability to make base mouldings that compliment waist mouldings that compliment cornices. A few pairs will offer the end-user so many options and, once mastered, confidence.

Confidence seems to be one thing that many of us lack. Starting a project is the hardest part. Completion just seems to happen.

If you are looking for specific suggestions: I am often asked what pair of hollows and rounds to get first. With two pairs you will be able to do by far more than twice as much as you can do with one pair. Not only will you be able to make the same profiles in two different sizes, but you will also be able to mix and match the profiles. With one pair you can make 30+ different profiles. With two pairs you can make well over 100. With two pairs you will recognize the true versatility that these planes allow and encourage.

If you do not know what sizes you want but there is a certain profile you want to execute, find the included radii and you will have the answer. Otherwise, I often recommend getting a pair of #4s and 8s (they cut a radius of 4/16ths and 8/16ths, respectively) if you’re starting with profiles included on pieces that come up to your waist; 6s and 10s are a good size for somebody that makes mid range furniture (chest of drawers). Both will likely be included in the largest highboys, secretaries, case clocks and your final set.

- How did the book for Lost Art Press come about?

I used to go to woodworking shows and demonstrate the tools that I make. I was able to introduce and inspire woodworkers with the ability of the tool but my explanation did not always translate into their work. Six months later I would see the same people and was told that, despite fully understanding the process we previously discussed, they had forgotten.

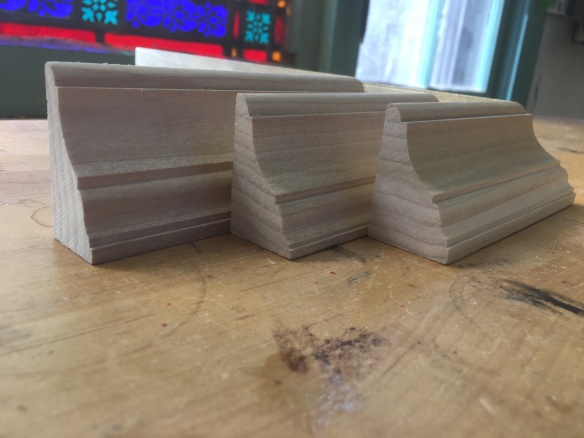

Profiles examples roughed in and ready for planing

I had started writing a pamphlet to hand out at the shows that I attended to people who seem inspired. This turned into me deciding that I would just put all of the information online, which I do through my blog. Chris Schwarz, the proprietor or Lost Art Press and who was very encouraging since the start of my business, read my blog for awhile and liked my approach and writing. I told Chris that I had essentially already started the process when he asked me if I had considered writing a book. The book then happened.

You did not ask this, but I have always been extremely proud of the book because I wrote every word in it. I have friends who have written articles and books. They produce a series of sentences that are then edited into the publisher’s words. Chris offered many suggestions but gave me full control over the book. He did not rewrite my sentences. He took out commas, broke up run-on sentences, comma-splices that are likely included here, and highlighted repetitious phrases, but the words are my own. Each of the books that Lost Art Press produces is unique in this respect: you seem to get the authors’ thoughts but the publisher’s directness. Each word in the final product has meaning and moves the narrative forward.

Moulding profiles cut with simply hollows and rounds