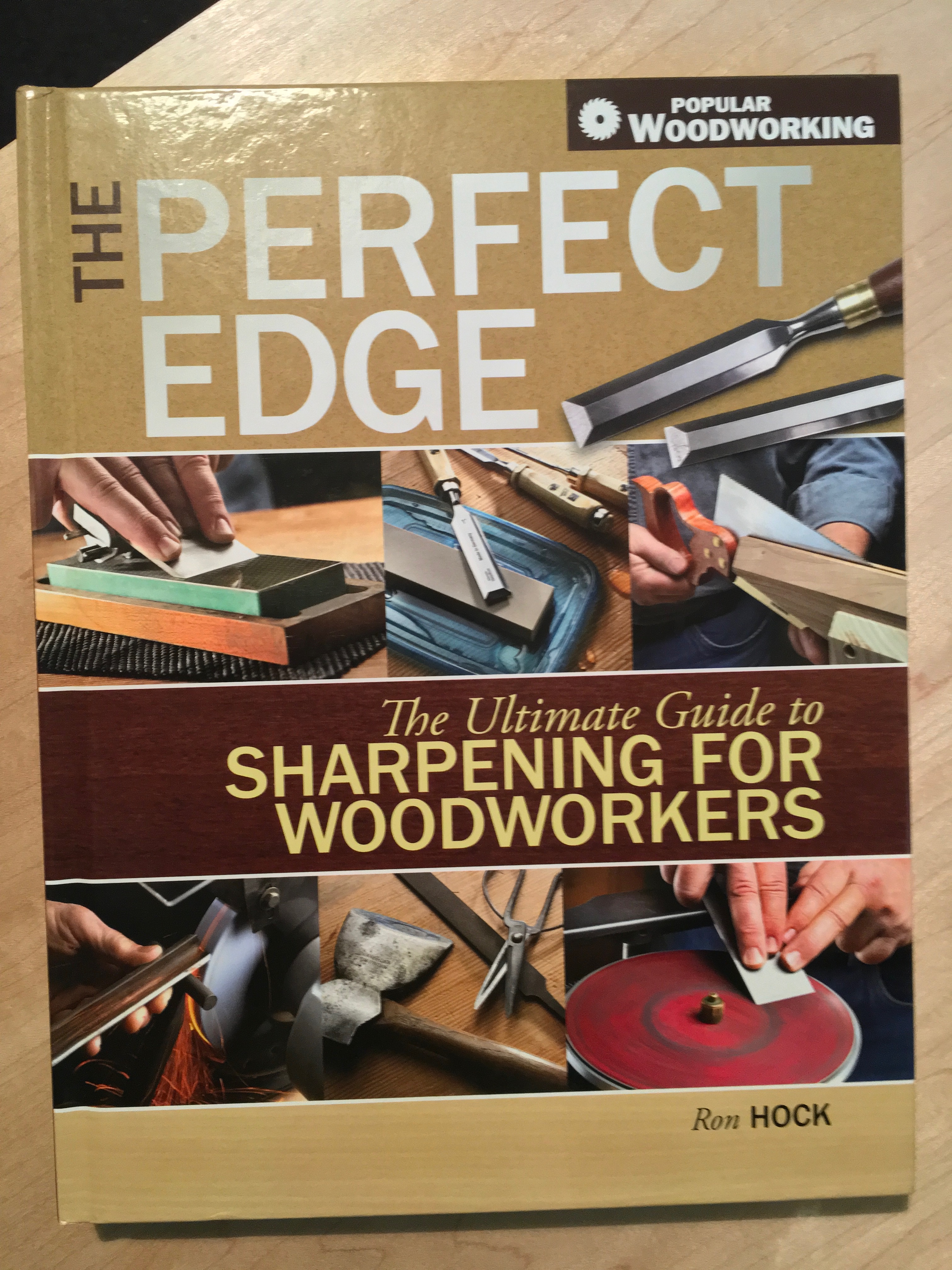

The following is based on an article originally published in Furniture & Cabinetmaking Issue 280.

The Lie-Nielsen No62

When it was first unveiled in 1905, Stanley’s No62 bench plane must have caused quite a commotion. Looking like nothing else in production, the No62 married the bevel-up blade orientation of a block or mitre plane to a bench plane sized body, measuring 14” long by 2” wide. While Stanley ceased manufacturing the No.62 in 1942, bevel-up bench planes have enjoyed something of a modern revival, thanks in large part to Karl Holtey’s revolutionary No98 smoothing plane, which prompted a reconsideration of bevel-up designs as being highly practical instead of an evolutionary dead end. So popular has the bevel-up concept become that premium plane manufacturers Veritas and Lie-Nielsen now manufacture a whole range of bevel-up smoothing, jack, and jointer planes. Returning to the plane that started it all, there are woodworkers who claim that the No62 is so versatile that it can replace the full set of traditional bevel-down planes. Never one to shy away from a challenge, I decided to test this claim by putting away my usual set of planes and spend several months using just a No62.

An Introduction to Blade Geometry

Before we delve into the test, it is worth explaining blade geometry, and the claimed benefits of a bevel-up bench plane. Traditional bench planes orientate the iron so that the bevel is facing downwards towards the bed of the plane, and the back surface of the iron is facing to the front of the plane. In this arrangement the cutting angle of the iron is determined by the angle of the frog of the plane, rather than the angle of the bevel honed on the iron. In contrast, a bevel-up orientation places the back of the iron against the bed of the plane, and the cutting angle is derived from adding the bed angle to the angle of the bevel.

Jointing oak

Blade orientation itself does not affect the performance of the plane – the wood does not care whether your plane is bevel-up or down, all it sees is the cutting angle. But different cutting angles will have different effects on the planed surface, and this is where the benefits of a bevel-up plane become apparent. A low cutting angle of 37 degrees is effective for cutting end grain, while a high cutting angle of 62 degrees will help to smooth difficult interlocked or figured grain. Because the cutting angle of bevel-down planes is determined by the frog angle, changing the cutting angle requires fitting a new frog, or honing a back-bevel to the plane’s iron. In contrast, the cutting angle of a bevel-up plane can be adjusted by honing a different bevel angle to the iron, or keeping a set of irons with different bevels for different tasks. Woodworkers enamoured with bevel-up planes suggest that having a single plane and collection of irons to achieve different cutting angles saves both space and cost when compared to a set of traditional bench planes, and by swapping out the irons, can achieve the same level of utility as a set of three bevel-down planes.

The Challenge

My usual stable of planes consists of a No.3 smoother, No5 jack, and No8 jointer – see “Curing Plane Addiction” for a detailed explanation of how to select a set of bench planes, and the purposes each one fulfils. Replacing those planes was a Lie-Nielsen No62 kindly loaned to me by Classic Hand Tools. The Lie-Nielsen plane is of comparable dimensions to the Stanley plane on which it is based, and the same size as a No5 bench plane – 14” long with a 2” wide iron. The mouth aperture is easily adjustable by twisting the front knob to allow the front plate to be slide forward or back for a tighter or more open mouth. The bed angle is 12 degrees, which means that honing a 35 degree bevel (as I do for most of my planes and chisels) achieves a 47 degree cutting angle very close to the “common pitch” cutting angle of most bevel down planes 45 degree. This low bed angle also explains why bevel-up planes are also commonly referred to as “low-angle planes”. Honing a primary bevel of 25 degrees results in a cutting angle of 37 degrees, which gives excellent results on end grain, and a 50 degree bevel results in a 62 degree angle for smoothing tasks. A 90 degree bevel effectively converts the plane into a large scraper.

So much for the theory, but what I wanted to know was would the No62 be able to discharge all of the tasks I used my familiar set of planes for?

The No62 works well as a jack plane, although you need to hone a significant camber into the iron to get it performing sweetly in this role

In Use

Broadly speaking, bench plane work falls into three categories – coarse, medium, and fine work such as flattening rough stock, jointing edges for gluing, and smoothing surfaces for finishing (see “Coarse Medium & Fine” ). In order to give the plane a thorough test I needed to press it into service on all three categories of work. Fortunately, I was about to start building a child sized stick chair in hard maple, as well as preparing larger sized stock for the Back to the Bootbench project, and a bookcase in maple. Between these projects, and working on an oak chair I was finishing off, the No62 would get plenty of use across a number of different operations.

First up were the coarse operations – flattening hard maple for the seat blank, and the larger pine and maple boards. Opening the mouth wide and setting the iron (honed with a 35 degree bevel) to a rank cut, I found that the No62 works as a respectable jack plane to hog off material and flatten rough stock. As with a bevel-down jack plane, a cambered blade makes processing rough stock a more efficient experience. The toothed blade definitely helps tame difficult grain at a “common pitch” cutting angle, and would be invaluable if rosewoods or heavily figured maple were part of your daily workflow. As it was, flattening stock was a straight forward process for both maple and pine, and I didn’t miss my usual Clifton No5 jack plane in the slightest.

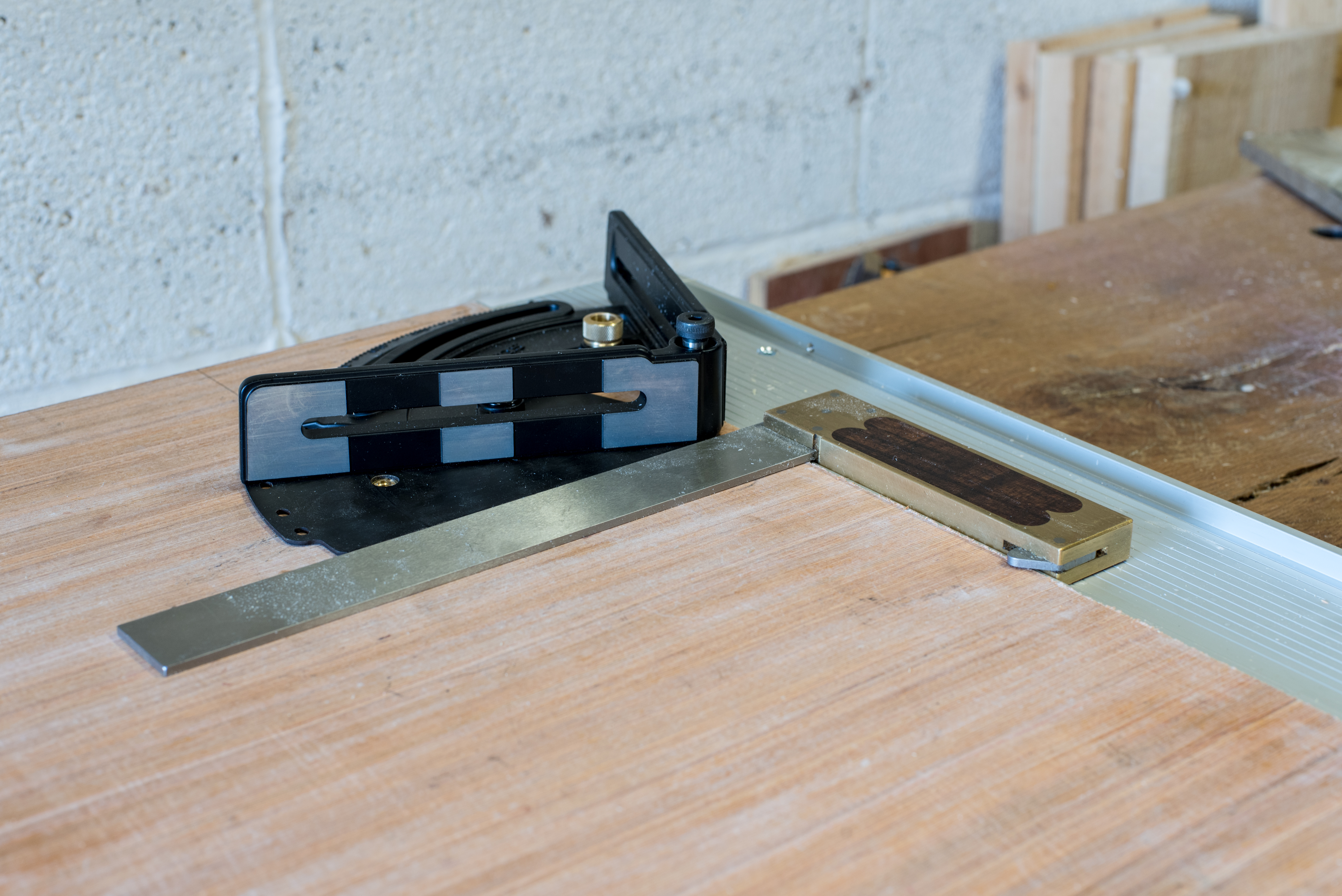

Italso functions well as a shooting board plane

Next came the “medium” work. Jointing the maple seat blank was also straight forward, closing the mouth and using the same “common pitch” cutting angle iron made short work of getting a square and straight joint on 2” wide, 17” long boards. At 14” long, I found the No62 a bit too short to use as a dedicated jointer plane on larger stock – the bookcase required 42” long edge joints to blue up panels, and while it is certainly possible to do this with a shorter plane, I did long for my 24” long No8 jointer for this work. One advantage of the No62 over my usual planes was the centre of gravity. The lower angle of the iron together with the lack of frog, means that the centre of gravity of the No62 is lower than for a bevel-down plane. While not critical for many operations, this lower centre of gravity was a real boon when planing 45 degree chamfers around the perimeter of the chair seat – a task I find can be awkward with a bevel-down jack plane.

The low centre of gravity is an excellent attribute when planing chamfers

Finally was the “fine” work, and it was when shaping the chair seat and legs that the No62 really came into its own. The seat is trapezoidal in shape, with nearly 12” of end grain on each side to plane. I smoothed the top of the seat with an iron honed to 50 degrees, and quickly achieved that familiar glassy surface that can only be the product of a really sharp smoother on hard maple. Switching to a 25 degree bevel angle rapidly cleaned up the large expanse of end grain and left a very clean surface behind. The lower centre of gravity was also really beneficial when shaping the legs into tapered octagons, as it was easier to balance the plane on the narrow faces of the workpiece and plane at a consistent angle. Smoothing the larger pine and maple panels was an equally satisfying experience, and the No62 worked really well as a large smoother.

The Only Bench Plane You Need?

So, is the No62 truly the only plane you need? To be honest, given the variety of approaches to woodwork, this is an almost impossible question to answer. But here is what I found during my two months spent using only the No62. It performs well as a jack plane, and excels at planing end grain and working as a large smoother. The ability to swap out blades to make an immediate change to cutting angle is very effective, and certainly represents a cost-effective way of adding smoothing and jack planes to your tool chest. The No62 does handle a little differently to bevel-down planes, particularly the tote angle and the location of the adjuster (which I found less intuitive). If unsure which you prefer, I would recommend testing a No.62 before purchasing. Once I had got used to the feel of the plane compared to my regular jack plane, I enjoyed working with it and found it very easy to use.

Levelling a chair leg with the plane held in the vice. This is a trick I picked up from chair makers Peter Galbert and Bern Chandley

At 14” long the No62 is larger than I would really want for a smoother to follow my hand planed surfaces, and a bit too short to serve as a dedicated jointer for furniture casework. Ideally a smoother should be small enough to reach any subtle hollows in a hand planed surface, and a long smoothing plane will remove the top of any undulations, requiring more passes before it can reach the low spots. This is less of an issue for stock that has been machined straight and flat, but makes the No.62 a little less efficient as a smoothing plane for a woodworker who wants to do all of their own planing. The toothed blade was very helpful for dealing with truculent interlocked grain, and would be invaluable if working difficult exotics was a daily part of your workflow (I have a toothed blade for my No5 for exactly this purpose).

In short, if I had a machine shop to flatten, thickness and joint rough stock, then I could easily see the No62 being my most used plane. Similarly, if most of my work was building chairs or musical instruments, then the No62’s ability to handle both end and difficult grain would make it a key tool. I would not want to be without a full-sized jointer plane for jointing long pieces, but again, if you had access to a jointer machine this would be less of a drawback.

The low centre of gravity is also helpful when planing tapered chair legs

As it is, the No.62 has definitely earned a place in my tool chest (particularly for chair making where it really excelled) but wouldn’t tempt me to sell my existing smoothing, jack or jointer planes. For the machine-based woodworker who is looking to add a quality hand plane to their set up, a No62 would be just the ticket.