I have a confession to make. I think I might have a saw problem. By which I mean, I definitely have a saw problem. Specifically a back saw problem – in my tool chest you’ll find only the regulation issue two hand saws (a 1900 era Disston D8 rip, and the majestic Skelton Panel crosscut). But you’ll also find more than the three essential back saws. Now, on the whole I’ve managed to follow the principles in the Anarchist’s Tool Chest and have resisted the lure of buying unneccessary hand planes, or endless sets of chisels. But when it comes to back saws, well, Daddy has a saw problem.

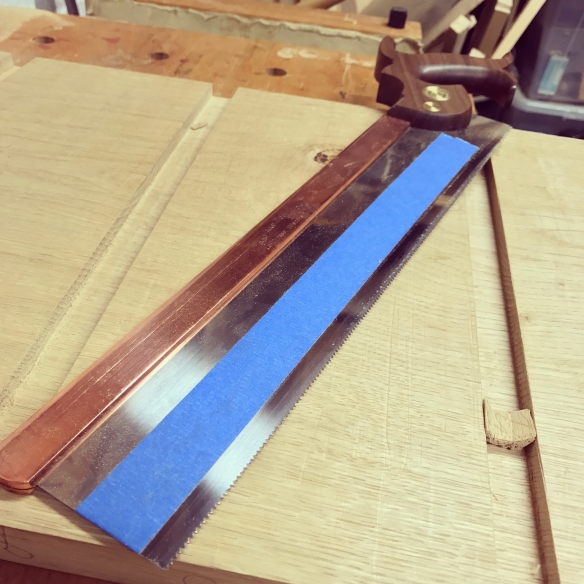

On the left my 10″ Doc Holliday dovetail saw, and on the right the 14″ Bayonet

The interesting thing about having a healthy collection of any one type of tool is that I find it prompts questions about how necessary each iteration of that tool is, and whether you could live with far fewer. And I spent plenty of time in the workshop before I owned a decent back saw, so it is possible to do so – not that I’d want to relinquish all (or any) of my saws. Each of my back saws sees heavy use, so they are necessary and I’m not about to thin out the herd. But still, the question of what a more compact kit would look like is an interesting one. Recently I think I may have found the answer. For context, my nest of saws contains the following back saws, all made by Bad Axe Tool Works: 10″ dovetail, 12″ carcase, 16″ tenon, 20″ mitre, luthier’s saw, and most recently, the Bayonet. So hardly the stuff of legendary excess. Like I said, a healthy collection.

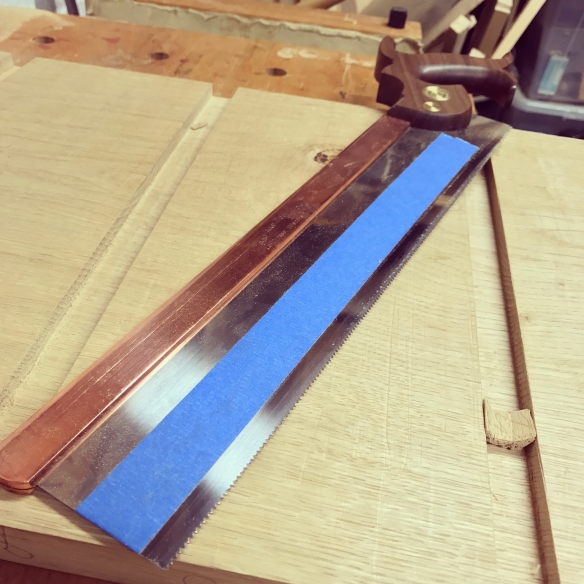

I’ve been using the Bayonet as my sole back saw on the Policeman’s Boot Bench and the more time I spend with this saw, the more I’m convinced that it is not only the perfect first serious saw for the woodworker building their nest of saws, but also the foundation of a compact yet highly functional set of saws. For the uninitiated, the Bayonet is a 14″ back saw which Bad Axe bill as being a “precision carcase saw“. The 0.18″ gauge saw plate is 2″ deep at the toe, canting to 2 1/2” deep, and comes with a Disston style open tote. I had mine filed with Mark’s “hybrid” filing for cross-cut and rip sawing, and tricked out in a very pretty copper back as a loving tribute to the Apprentice’s flame coloured hair.

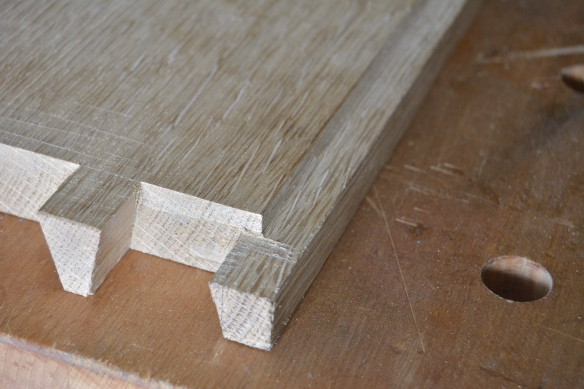

The Bayonet cut all of the dados for the Policeman’s Boot Bench with ease.

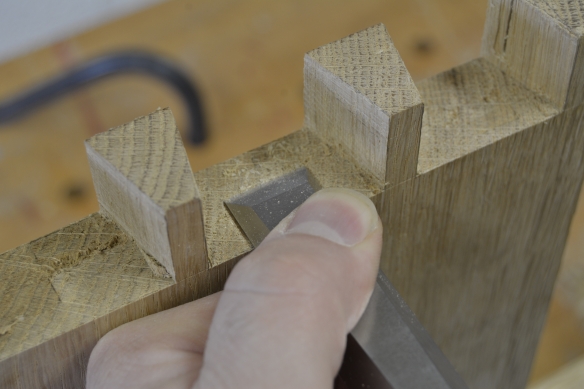

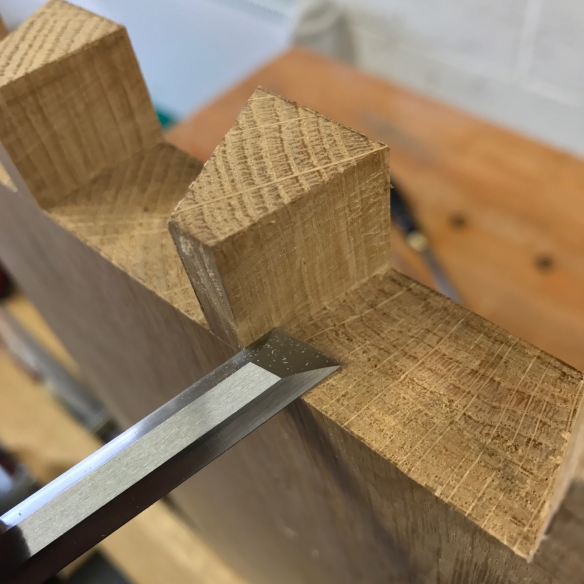

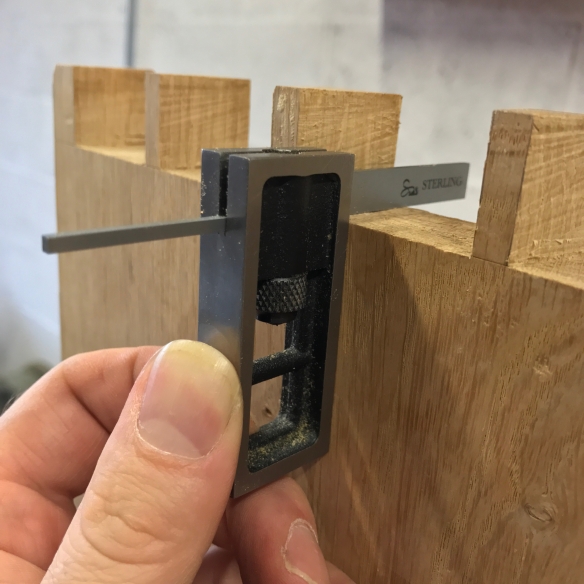

The initial reason I ordered the Bayonet was to cut the dados to let the shelves into the Policeman’s Boot Bench. The Bayonet was designed to cut all manner of carcase joinery, and so it shouldn’t have been a surprise that it excelled at this task. And yet, the ease with which it cut 1/2″ deep dados in 14″ wide oak was astounding. Not just because the saw is sharp (although it is – the guys at Bad Axe really know how to sharpen), but also how effortlessly an accurately it did so. This goes beyond simple sharpness, and is a matter of some very clever design. The shallow saw plate, together with a carefully judged hang angle of the tote, puts your hand much closer to the workpiece. The result is a saw that dives into the work aggressively but with real exactitude, for a high precision cut. It sounds simple, but there is something verging on alchemy with the plate depth and hang angle on this saw.

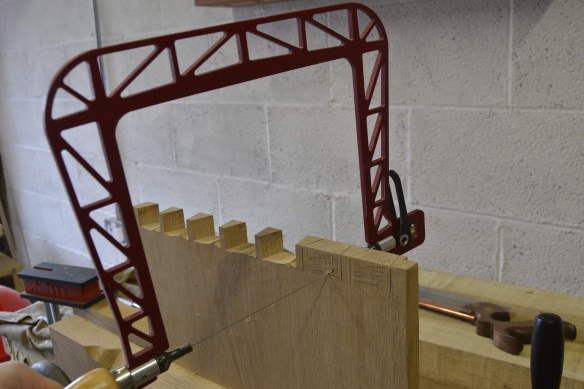

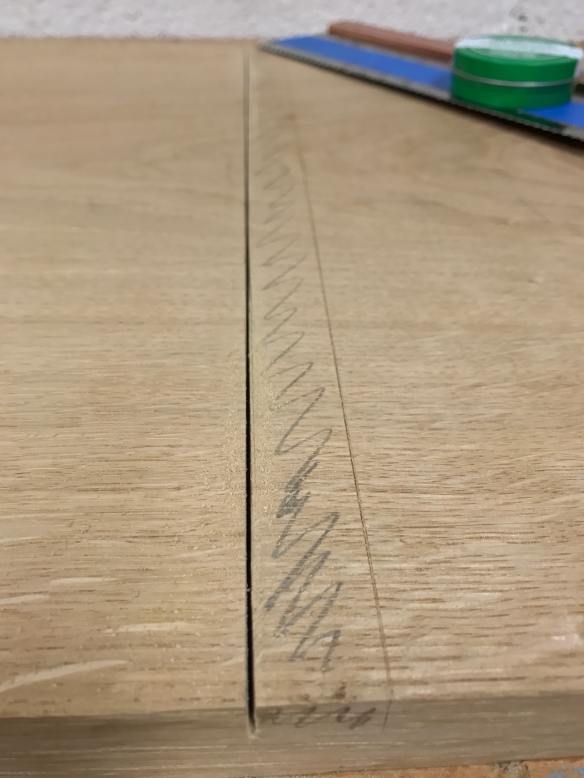

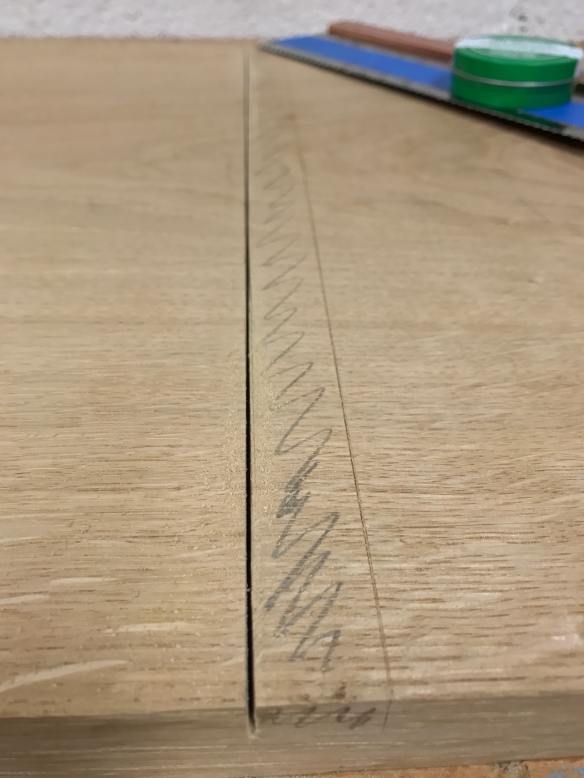

Whisper thin and arrow straight.

One risk when cutting across wide boards with a lightweight saw is that the saw can jump out of the cut until a kerf has been established. I’ve yet to have this happen with the Bayonet, which I’m sure is due to the lower centre of gravity created by the saw plate depth and hang of the tote. It has become a cliche to say that a saw tracks the line like it is on rails, but in the case of the Bayonet it is absolutely true – the first time I left a whisper thin, arrow straight, kerf across a 14″ wide board I was speechless.

Dovetailing

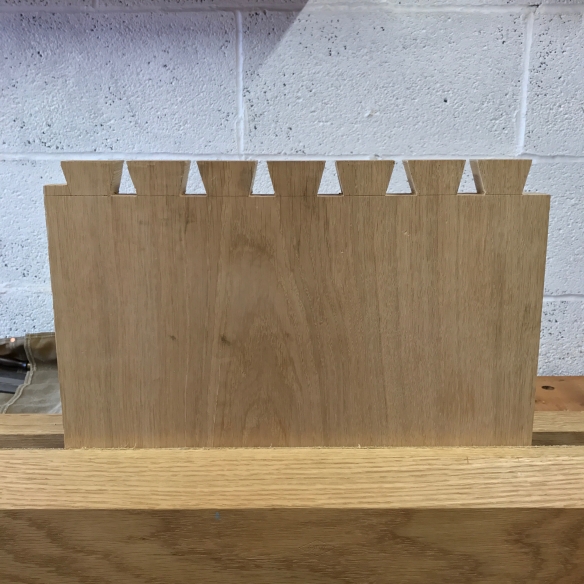

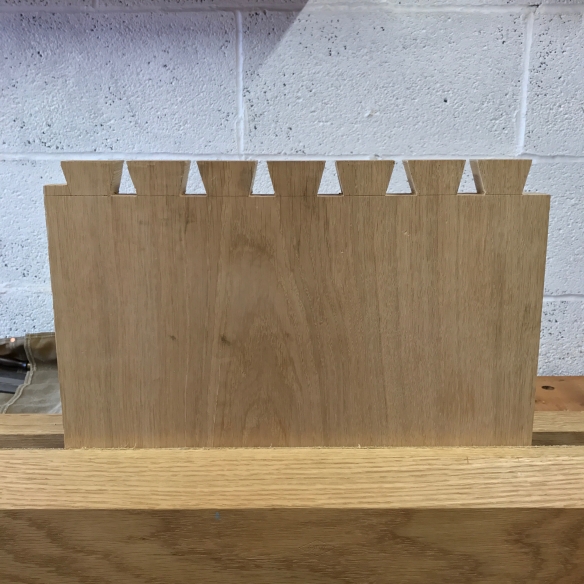

Having given the Bayonet extensive testing as a crosscut saw, I started to wonder how it would fare as a dovetail saw. Conventional wisdom is that a hybrid filing will be slower in the cut than a dedicated rip saw. This may be true, but in a head to head test with my 10″ Doc Holliday dovetail saw, the extra 4″ length of the Bayonet mitigated against any loss in speed from the hybrid filing. The extra length also benefits accuracy when splitting those layout lines, as most inaccuracies in sawing originate from the change in direction of the saw. By reducing the number of strokes needed, the potential for a wobble in sawing motion is reduced and the saw stays on line. Cutting dovetails with a 14″ long saw does require some slight adjustment to posture and body position, but with those taken into account I tested the Bayonet by cutting the tails for the Policeman’s Boot Bench. The saw left beautifully crisp kerfs in 1″ thick oak, and the saw was noticeably faster than my dedicated dovetail saw. The extra real estate on the saw plate also acted as a more efficient heat sink, which reduces the risk of overheating when making a number of repeat cuts and so keeps the saw plate free of heat related warping. I did not gang cut my tails as I often do, but I am sure that the Bayonet would have been able to take dovetails in a combined thickness of 2″ in its stride. In fact, the only discernable disadvantage I could find was that I had to be more careful when approaching the baseline as the extra length of the saw did increase the risk of overshooting.

Crisp tails, right off the saw

Will my existing carcase and dovetail saws be redundant? Not at all – they have other attributes which are beneficial for specific work, and for stock of 3/4″ thick or less the 10″ dovetail saw would be much more appropriate. But if I were looking to buy my first back saw then the Bayonet would be it – being able to cover rip and cross-cut joinery with one saw makes it a very cost efficient purchase, and means that the beginner would be able to handle whatever work they wanted to do without the need to save for a second saw in the a different filing. Similarly, the Bayonet makes for a very compact travelling nest of saws, as only a larger tenon saw would be needed to cover all bases. For classes or shows I’m certain that I will just be packing my Bayonet and 16″ tenon saw from now on. In short, this could well be the one back saw to rule them all.

Mark has also uploaded to the Bad Axe site a comprehensive knowledge bank covering all manner of saw care and maintenance, which can be viewed here. Even if you’re not in the market for a new saw, this page is well worth a view as it represents an invaluable distilation of Mark’s quite considerable knowlede, and a temendous gift to the woodworking community.