As every project nears completion I start to think about what finish will be the most appropriate given the timber selection, the location of the project, and the intended use. Some woodworkers have a favourite finish that they reach for as a matter of course, but I’ve never found that one magic finish. Sure, there are finishes which I really like for certain timbers or applications (water based lacquer for acoustic guitars, shellac and black wax for oak, milk paint for pine), but there is no one finish which I instinctively reach for. The benefit of being somewhat restless when it comes to finishing solutions is that I’m always open to trying new products or combinations.

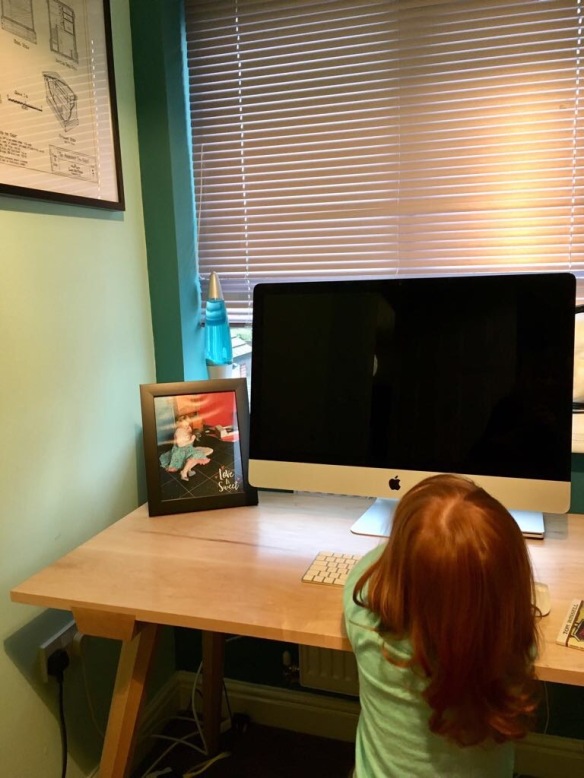

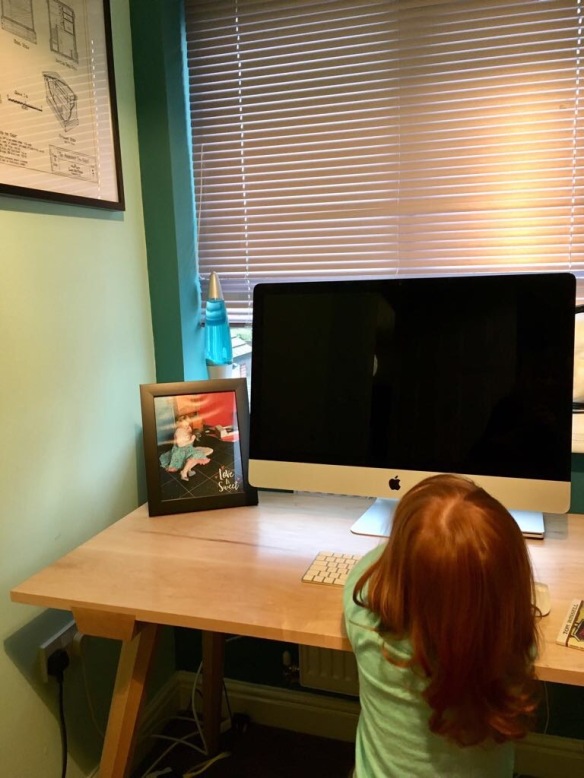

The completed work table in situ. Maple, sea foam green, and teal. All the hallmarks of a vintage Stratocaster!

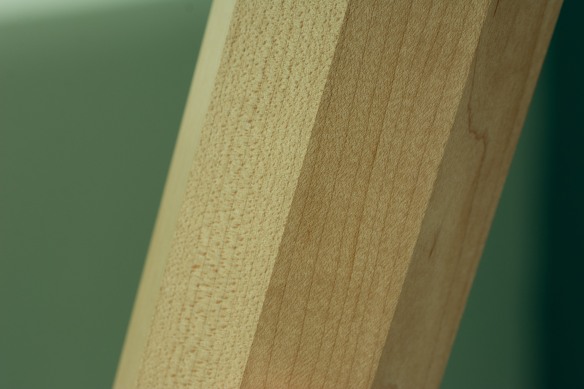

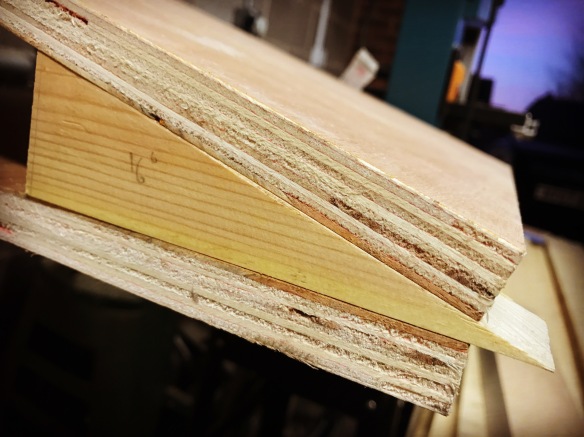

For the staked work table I planed up an offcut of the top as a sample and divided it into quarters. I like to have a couple of options to choose from, and with my sample board prepared I tried varying combinations of blonde shellac and hard wax, blonde shellac and Osmo Polyx, and a choice of either Osmo Polyx or Osmo Raw directly onto the maple (with no shellac). What I was looking for was a finish that subtly displayed the figure of the maple, but which did not add a high sheen – I will spend a lot of time working at this desk and don’t want to be distracted by light reflecting off a high gloss finish or by the figure becoming too loud.

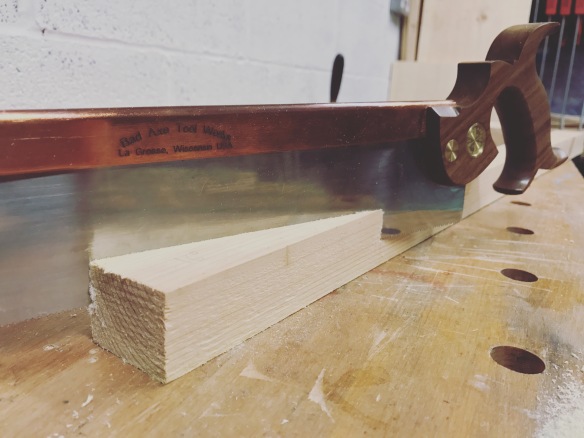

Applying shellac with a rubber

After living with the sample board for several weeks I decided that a base coat of blonde shellac with a top coat of Osmo Polyx matt would achieve my desired criteria. The shellac lifts the subtle curl of the maple top but never becomes too brash, while the Osmo adds a low-sheen protective layer which will ensure the longevity of the desk.

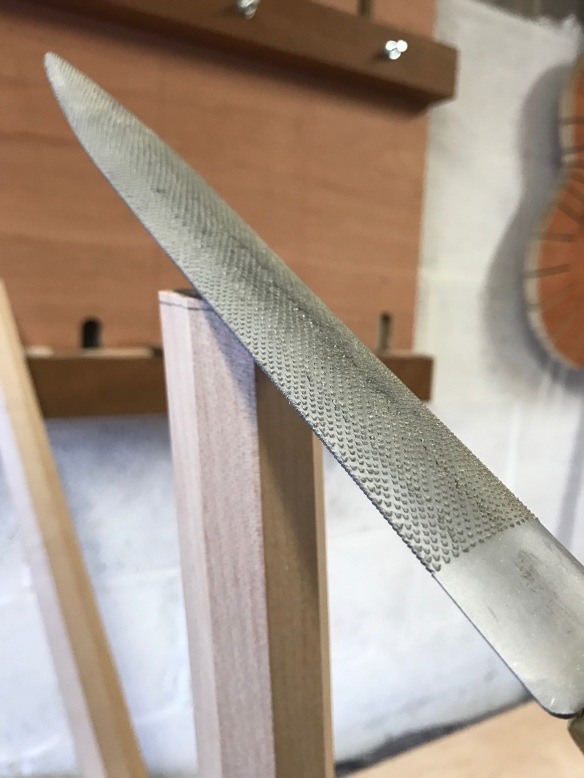

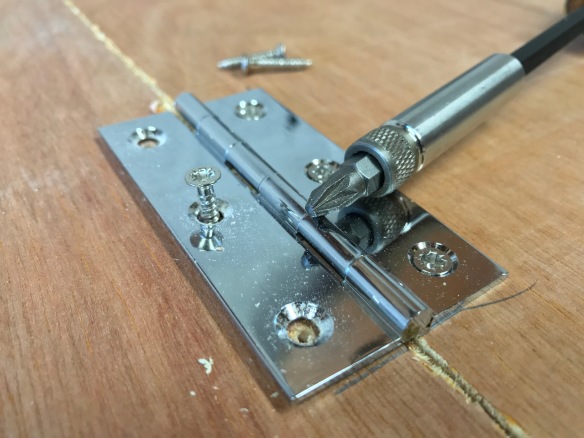

Before I applied the finish I spent some time checking the assembled desk and making pretty; cleaning up glue squeeze-out from the batten sockets, flushing up the front of the battens with a smoothing plane, and removing any last traces of tearout with a cabinet scraper. Finally, I broke the sharp corners of the desk top with 220 grit sandpaper. This last step is both for my comfort (maple can take a wicked sharp edge when planed) and to reduce the risk of the aris breaking in use.

The top after two coats of shellac. Now for the Osmo.

Most of my finishing solutions tend to be quite simple – I want the finish to look good but I also want it to be easy to apply, and this was no exception. Previously I’ve applied shellac using a good quality polishing mop, but after some sage words of advice from Derek Jones (Derek really knows finishing) I decided to try applying shellac using a rubber. A quick order to John Penny Restoration later and I had plenty of lint free rags and skinned wadding to make the polishing rubber. Derek’s book provided a very useful walk through on how to fold the rubber and use it to apply the shellac. I used blonde tiger flake shellac from Tool for Working Wood, mixed to a 2lb cut. This went on very easily, and after two coats the figure on the table top was popping nicely without becoming brash. Using a rubber left a smoother texture than brushing shellac, which reduced the need for sanding between coats, and will definitely be my preferred method of applying shellac going forwards.

The final step was to apply the Osmo. I ragged generous coats on to every surface save for the underside of the top (which left with just a shellac coat) and then wiped off the excess after 20 minutes. Two coats applied 24 hours apart gave a good build up of finish and left a matt sheen which is attractive without being distracting.

Quality inspection by the Apprentice

After leaving the desk for another 24 hours to get rid of the worst of the chemical aroma of Osmo, I moved the desk up to my study. This is the first piece of furniture I’ve built for our house, and the first time I’ve decorated a room with a specific furniture project in mind. When I started to decorate the study I wasn’t sure what colour to paint the walls – it is a small room so I wanted something that made it feel light and vibrant. Dr Moss suggested that I look to my favourite vintage guitars for inspiration, and so the walls were painted sea foam green and teal (my two favourite vintage Fender colours) with the knowledge that the Anarchist’s Office Suite of desk, chair, and bookcase, would all be maple. Moving the desk in was the first opportunity to see whether this combination had the desired effect. I’m pleased to say that seeing the desk against the painted walls really does evoke a mid-1950’s Fender Stratocaster, so the concept worked!

But more than that, the desk is sturdy, comfortable, and provides a very generous working area. It is also a very tactile piece – the smooth top contracts wonderfully with the roughly scalloped underside, and it is wonderful to run your fingers over the facets of the legs.

Loaded up with my iMac and ready for work.

And so, I’m sitting in my study, typing the first of many blog posts which will be written at the new desk (not to mention magazine articles, and the small matter of the John Brown book). The study will continue to be a work in progress until I’ve finished the staked chair and bookcase to match the desk, but already it feels good to have a dedicated and comfortable place to work. I’ll be covering the progress of the rest of my Anarchist’s Office Suite over the coming months.