One of the big attractions of building the staked worktable was the tapered octagonal legs. As I’ve written before, I really like the way that tapered octagons reduce the visual weight of a leg while retaining the structural strength, and also how the introduction of facets plays with light and shade. This in turn informed the timber selection for the desk. A light toned timber such as maple reflects light and emphasises the silhouette of the design, drawing the eye to the facets in the legs. I briefly considered using a dark wood, such as walnut, for the same silhouette enhancing reason, although ultimately I thought that a dark timber could dominate what is a relatively small room. Heavily figured timbers were immediately discounted from the material choices for this desk, as a showy timber would obscure the overall shape of the design by drawing the eye away from the lines and facets towards the figure of the wood.

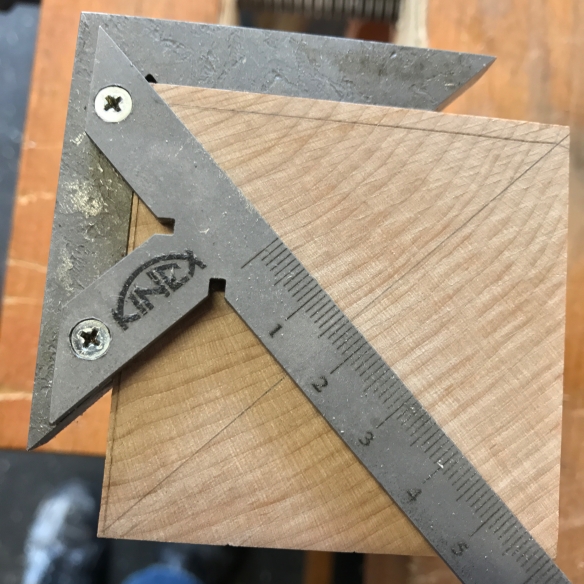

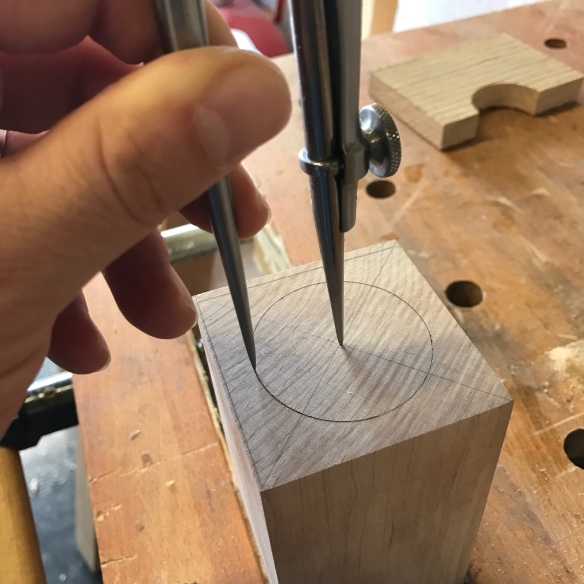

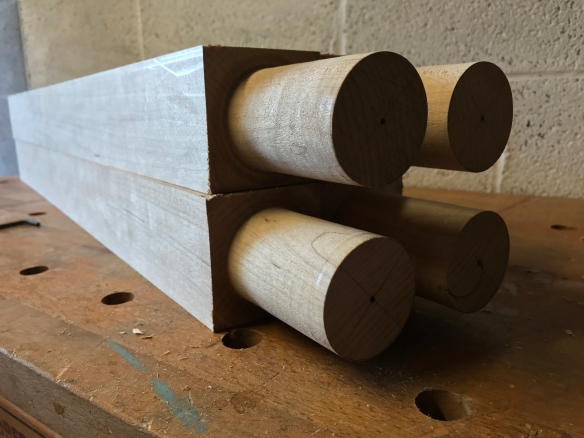

Laying out the foot. You can see the indentations from the lathe drive centre.

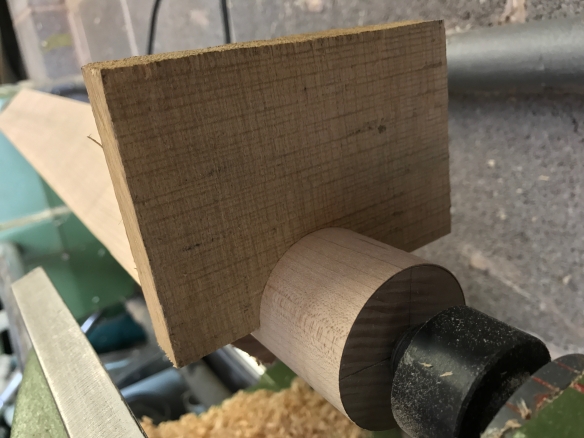

Octagonalising the desk legs is broadly the same process as for the staked saw bench legs, only on a significantly larger scale. Before planing in the octagon the legs need to be planed to a tapered square profile. In the Anarchist’s Design Book Chris suggests that a bandsaw is used to achieve the tapered square cross section, and also explains how a powered jointer (or planer, if like me you’re English) can be safely used to create a tapered surface. I need to fit a new blade to my bandsaw, and to adjust the tracking (something I’ve been meaning to do for a while now) so I decided to taper the legs the old fashioned way.

Hogging off the waste with the No.5

To lay out the cross section of the foot I used a pair of dividers to scribe a circle with a diameter of the final foot width, and followed up with a small square to mark off the four sides of the final foot. Selecting one face to plane first, I marked on the two adjacent faces lines showing the full length of the taper from the tenon shoulder to the foot. The bulk of the material has to be removed from the foot, with the least being removed from the tenon shoulder. I find it easier to plane a taper by working off the workpiece rather than onto it, and so started by hogging off the waste at the foot with the No.5, set to an aggressive cut. It doesn’t matter at this stage whether you’re planing with or against the grain, nor does it matter if you get tear-out at this point, as there will be plenty of time to refine the surface once the majority of the material is removed. The focus is just on removing the waste quickly and efficiently. As the waste comes off the foot, lengthen the plane strokes to keep the taper straight and flat – the plane wants to create a curve which would result in a visually bulging leg. The key is to changing the pressure from the toe to the heel of the plane as you move through the cut.

Refining the taper with the No.8 jointer

Once roughly half the waste is removed from the foot, and the cut has advanced to half the length of the leg, I moved from the jack to the No.8 jointer plane set to a medium cut. At this point I work with the grain, even if this involved planing uphill (from the foot to the tenon shoulder) onto the workpiece. The taper increases the length of the leg until a full-length shaving is taken from the foot to the tenon shoulder. Checking the surface with a straight edge helps, but the plane shavings and layout lines on each side of the leg should be enough to tell you if the taper is square and true. As I get closer to the layout lines, I keep reducing the depth of cut on the plane, until the final few shavings are full width, very fine smoothing shavings. I found that for tapering all four sides of the legs is pays to rotate the leg in a consistent direction for each subsequent face, as this means that after the first face, you are planing a smaller surfac area (because one of the adjacent faces has already been tapered) and the fourth face will be smaller still because both adjacent faces have been tapered.

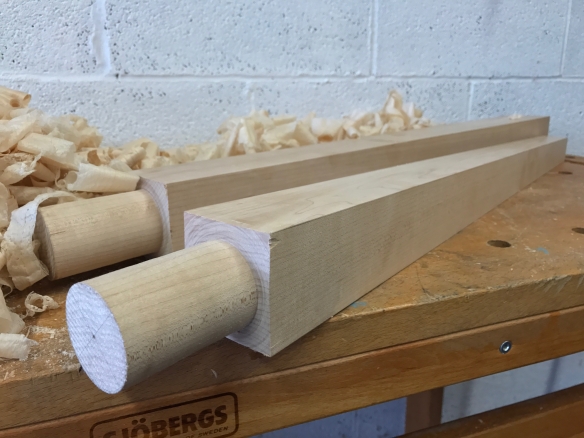

Not a bad amount of shavings from just one leg

I didn’t quite appreciate when I started tapering the legs just how much material was going to be removed – the taper is much more pronounced than for the staked saw benches. This may explain why Chris suggested a bandsaw would be a fast way to achieve the initial taper before octagonalising the legs. That being said, the handtool only approach isn’t too slow providing proper use is made of the jack plane to rapidly remove stock and before finishing up with the jointer. The dramatic taper on the legs is going to be really striking on the finished desk, and I’m looking forward to planing in the additional facets for the octagons.

Comparing a tapered leg with a square leg shows just how much material is removed.