I’ve put the parlour guitar to one side temporarily while I work on a couple of more urgent projects – the Mystercaster (the customer for which has been very patient with me) and also a couple of builds for Furniture & Cabinetmaking. I’ll continue to work on the parlour guitar in between those projects, and it has definitely not fallen by the wayside.

I really enjoyed my first Telecaster build. Electric guitar builds, particularly the classic Fender designs, are a very different workshop experience to my more usual acoustic guitars. This is in part due to the increased use of machinery – you could go hand tool only building an electric guitar, but cutting the body to shape in 2″ thick timber wouldn’t be much like fun. And Leo Fender deliberately designed the Telecaster and Stratocaster to be easily built with the technology available to him – they were after all the first production guitars. So this was an interesting process for me, given that I am very much a hand tool focused woodworker. And I’m sure I’ve said it before, but the tool I like using the absolute least in my workshop is the router – the thing just plain terrifies me. So when I first started building Laurie (my first Telecaster) there was some tension between the best way to build the instrument, and my prefered approach to lutherie. I’m not for one second saying that using machines is bad and wrong – many people make wonderful instruments and furniture with machines. But for me that is not a process, or an approach, which I find particularly satisfying (and again, see the blind terror or switching on the router). So for Laurie I forged a path where some operations would be fully powered – for instance shaping the body and fitting the truss rod, but as much as possible would be hand tool work. This hybrid approach worked well, and I’m looking forward to refining the same approach with the Mysterycaster before I retreat to some hand tool only projects.

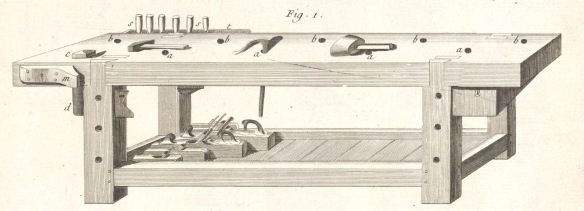

This is the body timber before I started planing. More gaps than the proverbial beaver with a meth habit.

My first task for the Mysterycaster was to joint the two halves of the swamp ash body. When edge jointing, before I introduce a plane to the work I find it useful to assess the extent to which the joint will need flattening, firstly by holding a straight edge to the edge of the workpiece, and then by holding both the two edges of the joint together and seeing where the gaps fall. Unlike edge jointing for furniture, where a spring joint can be used, and it is common to leave a very faint hollow across the width of the joint, jointing for electric guitar bodies requires a joint that is deadnuts flat across both the width and the length of the joint. This is so that the glue joint does prevent the two halves of the guitar from resonating properly, and so that you don’t get any nasty surprises when surfacing and thicknessing the jointed body. There are no special tricks behind getting a solid edge joint, just good planing technique and using a straight edged blade (rather than one with a gentle camber like some furniture makers use). A very useful technique I’ve found invaluable for edge jointing is making stopped cuts without leaving a step behind – courtesy of Chris Schwarz’s Popular Woodworking blog. Edge jointing can require working localised highspots, and a stopped cut is the perfect way to do this. However a poorly executed stopped cut can leave a stepped transition which results in more gaps, not fewer. Chris’ technique for starting the cut with no downward pressure on the plane, and lifting the heel of the plane off the work (instead of the toe) at the end of the cut worked perfectly, leaving a smooth transition across my stopped cuts.

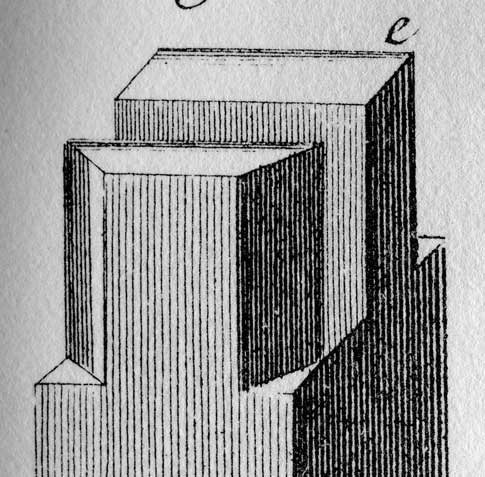

Flat across the width, and square to the face of the workpiece.

My prefered plane for edge jointing is the Lie Nielsen No.8, partly for it’s excellent length (which helps to keep long edges straight) but also the wide blade which makes edge jointing even the 47mm wide swamp ash I’m using for the Mysterycaster a pleasure.When edge jointing I check my progress constantly, mainly with a straight edge to check the length of the joint for flatness, and the diagonals (corner to corner) to make sure I’m not introducing any twist or wind into the joint. For checking that the width of the joint is both flat and square to the face of the timber, my Sterling Tool Works Double Square is invaluable. The best check however is against the other half of the joint. I worked one half of the body until it was 90% there, and then moved to the other half. Once both sides of the joint were very close I fitted them against each other and noted where there were any hairline gaps. It is important to check the back of the timber as well as the front, because one side can look perfect while still having significant gaps on the other.

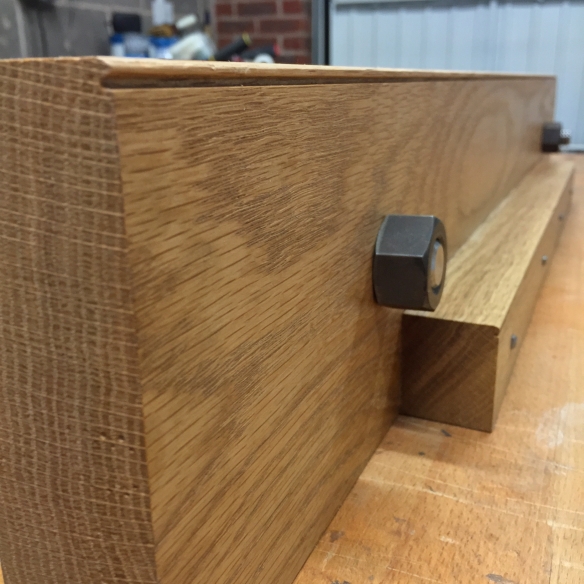

The finished joint – through a macro lens you can see where the joint falls because of the change in grain directions, but you can’t see the joint line.

Once I was satisfied with the joint, I resharpened my plane blade and took a couple of very fine cuts from each side of the joint (no more than 3 cuts per side). This last touch closed everything up nicely, and the joint looked good and tight from both sides. A thin layer of Titebond and one rub joint later, and the body is now resting in three sash cramps over night.