The new Bad Axe Luthier’s Saw

I find it hard to believe that I first floated the idea of a dedicated luthier’s saw to Mark Harrell three years ago, in many ways it feels like the conversation started much more recently than that. Slotting fret boards for guitars (and other fretted instruments) is one of the most critical stages of a build, determining whether the instrument will intonate properly. For all of the jigs on the market to help locate the cut at the correct point of the fret board, I’ve never understood why, or been satisfied with, the proliferation of cheap saws to make these most critical of cuts. And so I decided to reach out to the best saw maker I know and see if he was interested in giving luthiers a high quality saw which could handle fret slotting duties as well as other fine cross-cut work.

That conversation ended up lasting two years as specifications were circulated, adjusted, and ideas tested. We welcomed good friend and fellow luthier Susan Chillcott to the conversation, and continued to work through exactly what the specification for a fret slotting saw would look like. A protoype arrived on my workbench in March 2016, followed by the first production model in August 2016. And testing continued.

This is a test (this is very testing)

The best way to really get to grips with a tool is to live with it and test it on real life projects and in as many different applications or circumstances as possible. And here is what I found interesting – although the Bad Axe Luthier’s Saw was intended for fret slotting and other fine lutherie work, I’ve found myself reaching for it repeatedly for furniture work too. The depth stop was a real boon when cutting out the stopped dados in my School Box, and again came in handy when defining the tenon shoulders for the legs of my staked saw benches. So although this is marketed as a “luthier’s saw”, it is far more versatile than that, and is perfect for anywhere that a very fine furniture grade cross cut is desirable.

The Primary Mission

And yes, it slots fret boards too. Far better than any of the cheap (read: disposable) fret slotting saws I’ve used in the past. Mark’s skill in sharpening saws is no secret, and the luthier’s saw has been sharpened to perfection. The saw has that familiar Bad Axe balance of aggression and precision, requiring only a couple of strokes to cut to the appropriate depth for fret wire, and despite the aggression it still leave behind a complete absence of blowout on the exit side of the kerf. In fact, this saw leaves the cleanest kerf I’ve seen on a fret slotting saw, by some measure. And that hammer-set kerf has been dialled in to deliver a 0.022″ kerf for most modern fretwire tangs. On a precision tool like this, getting the fine details right is the difference between a saw that works, and something that looks pretty but will stay on the shelf. Bad Axe have got all of the details right, and this saw is a workhorse which will stay in my tool chest until I’m ready to hang up my apron for the final time.

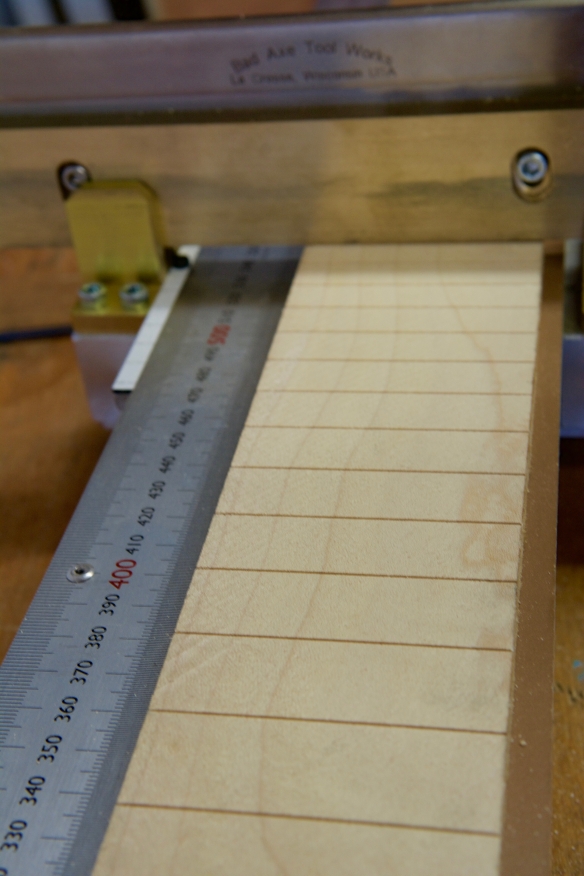

Slotting a maple fret board

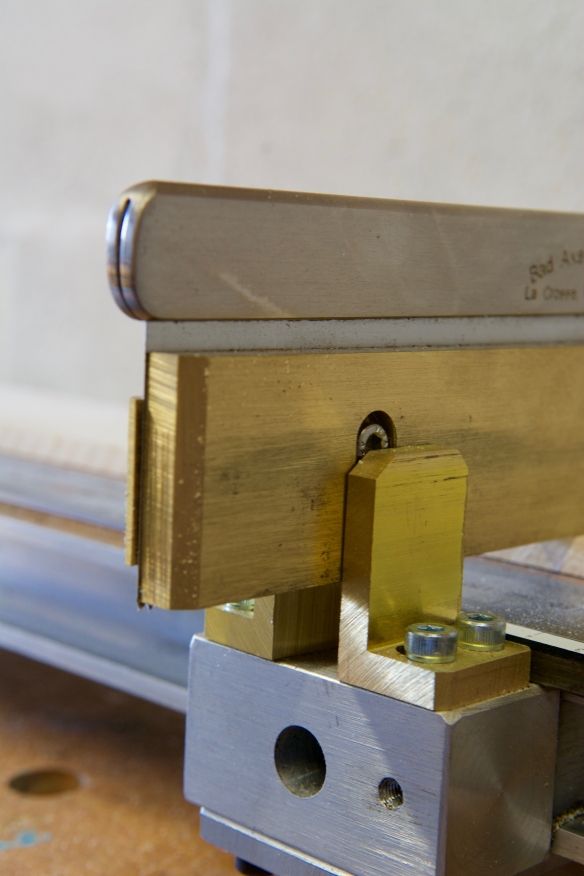

The open tote feels identical to my Bad Axe dovetail saw, and fits the hand perfectly with no hard transitions, flats or corners to cause fatigue, leaving you free to concentrate on the cut and not on the saw. Mark also did a great job on improving the plastic depth stop used by other fret slotting saws. The Bad Axe depth stop is substantially thicker than the plastic alternative used by other manufacturers, which gives a greater surface area to register on the workpiece, and instead of standard acrylic commonly seen, uses a Polyethylene polymer with a high lubricity. The difference is instantly noticeable – when you bottom out of the cut the depth stop glides across the work piece without catching or scuffing, preventing the saw from sinking deeper and leaving no mark on the work. The brass thumbscrews cinch down authorititvely and in many months of testing I never felt the deth stop slip in use.

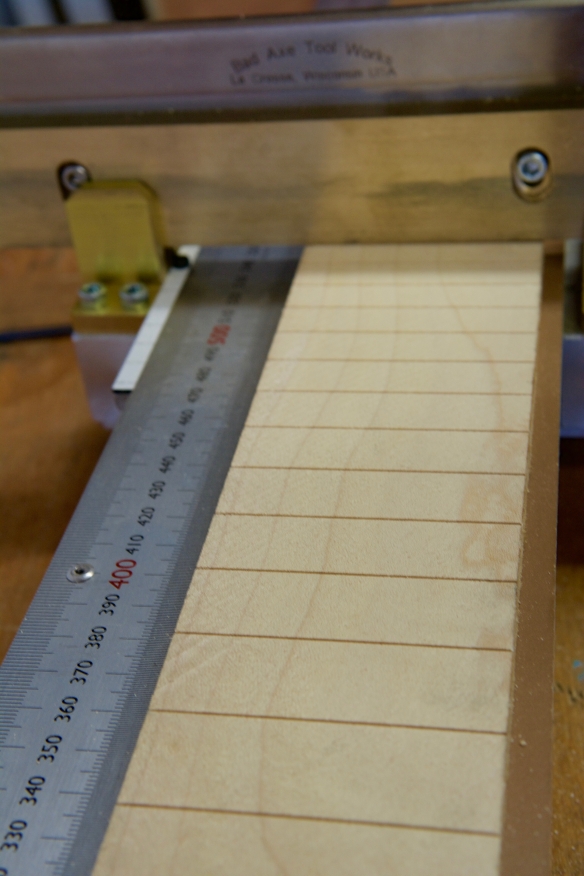

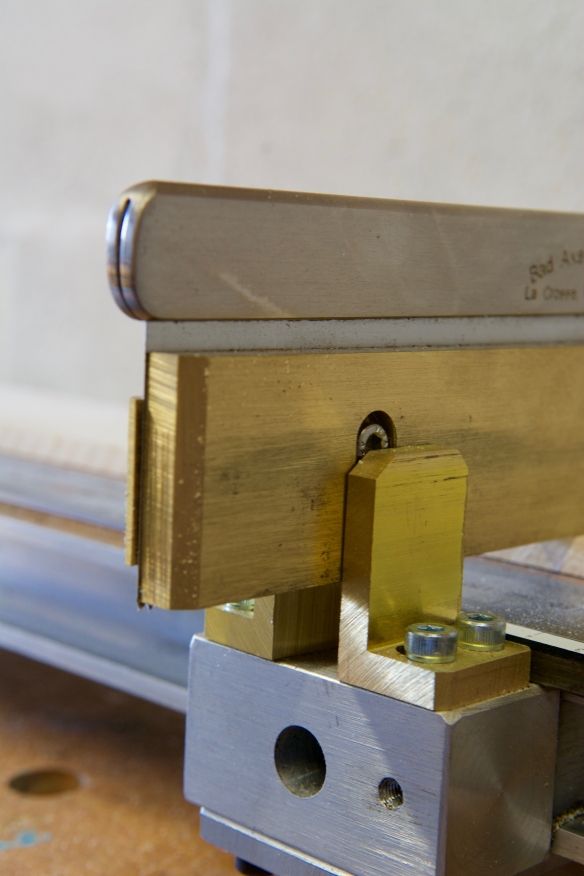

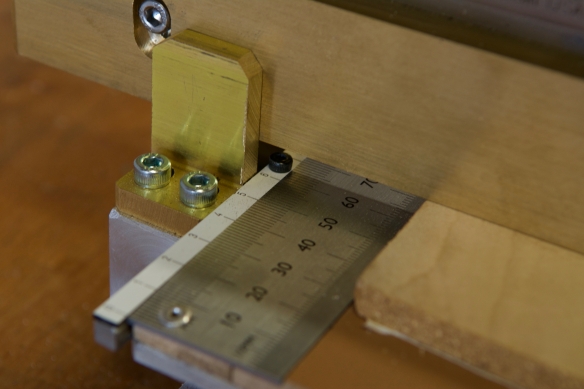

There are many ways to slot a fretboard, and many jigs which claim to make life easier. I recently took the plunge and ordered a fret slotting jig from Tony Wright, an engineer and luthier of 28 years, and the brains behind Necx Products and Lakestone Guitars. This is the same jig as we used in Totnes, and is the perfect pairing for the Bad Axe Luthier’s Saw. Most jigs rely on a guide board and locating pin arrangement to deliver the saw at the right location for each fret slot. This ties the user to just the scale lengths the jig manufacturer supports, and also requires additional cost (not to mention storing additional guide boards) if you want to build to a different scale length. In contrast, Tony’s fret slotting jig uses a vernier scale and a free moving carriage to move the saw along the fretboard, so any scale length can be cut without the need for additional accessories.

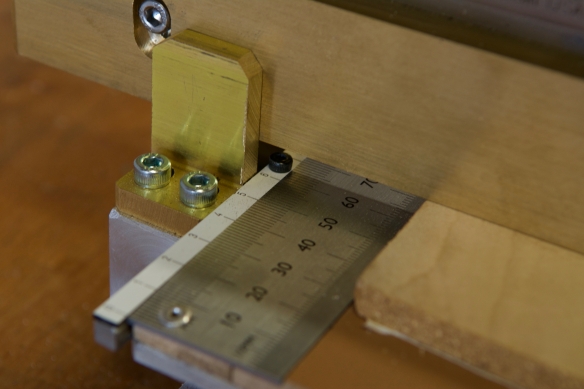

The vernier scale enables the user to precisely locate the saw for each cut

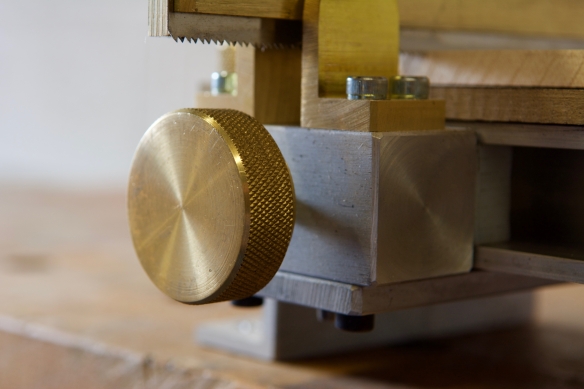

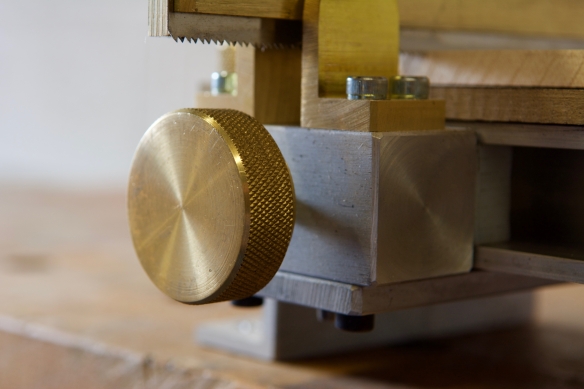

As a combination, this really cannot be beaten. The fine gearing of the carriage assembly on the jig means that the Bad Axe saw can be positioned by increments of 0.1mm before making the cut. When you have an incredibly precise saw, you only get the benefit of that precision when you can be targeted about where it is deployed. Having moved the carriage to the right location the carriage locks down tight with a large brass knob, and the cut can be made. All in all, a fret board can be cut with absolute precision in little more than 30 minutes.

The carriage locks down to prevent the cut from wandering

European Woodwork Show

I will have the Bad Axe Luthier’s Saw and the fret slotting jig with me at the European Woodwork Show next month, as well as a supply of fret boards. If you would like to have a go at slotting a fretboard do stop by and say hello.

The Luthier’s Saw is now on the Bad Axe website and is available for order.

Disclosure: I assisted Bad Axe in the design and development of the Luthier’s Saw, and my sole payment for that work is the saw pictured above. I receive no commission or payment based on future sales of the saw, and no payment for writing about the saw. All content on Over the Wireless about the Luthier’s Saw is my own unbiased opinion.