A workshop, very much like a tool chest, is never complete. I find that any significant reorganisation to the workshop tends to happen at the end of a major project – once I get deep into a project I don’t want to get distracted by other tasks, and a major project is also likely to highlight any ergonomic pinchpoints in my current set up. Post-project reorganisation reflects those learning points. The result is that a workshop reshuffle has become something of an end of project ritual.

My reorganised workshop, at least until the Roubo bench timber arrived

In the course of the staked work table and the saw cabinet builds the workshop had become rather unruely, and a deep clean and reorganisation were long over due. This became something like a game of solitaire, as large sections of the ‘shop were emptied out onto the driveway and things moved around until I had a clearer and much more ergonomic space. The thin panel jig and solera were moved from above my workbench and hung above the lathe – this keeps them out of the way but still accessible. It also means that the backdrop for any process photos is now just a white painted wall, without any cameo appearances from those jigs. The saw cabinet was then hung on a pair of french cleats to the left hand side of the workbench where it will be within a few steps whenever I need a saw (which is often).

The lutherie jigs now hand above the lathe

With the saws in the cabinet, I removed the old saw till from my Anarchist’s Tool Chest (prying out the battens really demonstrated just how tenacious cut nails are!) which opened up more useable floor space for the planes. I also moved the Golden Rod to the moulding plane corral. I do plan to fit another saw till to the tool chest at some point in the future, using the lighter weight design Chris wrote about earlier this year. But that will wait until I next need to travel with the tool chest. I also cleared out my lutherie specific tools from the Anarchist’s Tool Chest, and placed them in a new Clarke’s machinist’s chest, which sits on my sharpening station – these tools need to be stored safely and within easy reach, but I only need them for specific tasks and so it makes sense to keep them separate from the tools in my Anarchist’s Tool Chest.

The saw cabinet hangs to the left of my workbench. The Roubo bench will extend to underneath the cabinet.

The major addition to my shop last year was a new drill press. At the time I assembled it just where there was some clear floorspace, but it was far from the ideal location. So to find a proper home for it I collapsed the go-bar station and stowed that away for future use, and reorganised my timber storage corner. The drill press is now snug at the far end of the workshop, within easy reach of the bench but tucked away where I won’t keep backing into it.

This corner isn’t half as cramped as it looks here. Particularly as a lot of the pine has now been broken down ready for a project.

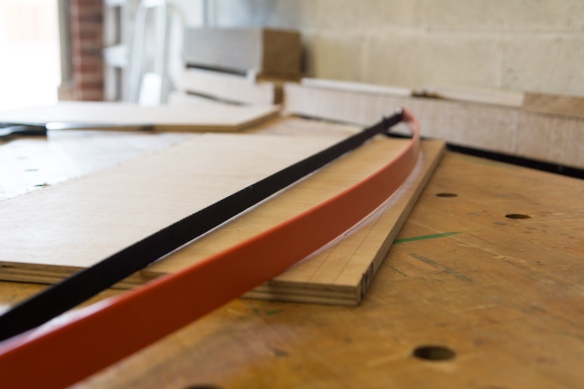

One of the pinch points I found on the saw till build was the amount of time I was wasting by hunting for my bench hooks and shooting board everytime I needed to cut and shoot stock. I had some fibreboard loft flooring left over from a house job, and I fitted two battens of scrap oak to the stretchers of my workbench, using a pneumatic nail gun. The loft flooring was cut to length and dropped on top of the battens, and now houses my Moxon vise, shooting board, bench hooks and lump hammer. This keeps a number of key appliances within easy reach, and has also added some much needed mass to my Sjoberg bench.

Not a tool I reach for often. But when it comes to jib building or attaching cleats, this pneumatic nail gun is fast and reliable

Finally, I added a second shelving unit behind the Anarchist’s Tool Chest, to hold power tools, finishing supplies, and the usual odds and ends you end up accumulating.

The shop is a lot more manageable now, with many essential tools and appliances within easy reach. That’s not to say it is finished (it’s never finished, remember?). Unfortunately by collapsing the go-bar station I lost my clamp storage, which means that I need to build a simple clamp-rack at some point soon. And the timber storage corner still needs a proper tidy. But it is a definite step in the right direction, and most importantly is now able to accomodate the Roubo bench. Since that initial re-organisation the timber for the Roubo bench has also arrived, and I’ve moved my bench 6″ away from the wall to accomodate the timber while it acclimatises.

A second shelving unit provides ample storage for finishing supplies, moving blankets, my lighting rig, and power tools. On the left you can see the machinist’s chest which houses my lutherie tools.

This has also helped to answer a quandry as to where the clamp rack and saw cabinet would go once the Roubo bench is finished, as the Roubo will be twice the length of the existing bench. My current thinking is that the new bench will sit in the current position I have my Sjoberg – roughly 6″ away from the wall. This will allow the saw cabinet to stay where it is without getting in the way when I am working at that end of the bench. A clamp rack can then be mounted to the wall at the other end of the bench, meaning that all of my clamps will be within easy reach but again. I think this should work, as the Roubo will have plenty of mass as it is, so won’t be inclined to dance across the workshop like my Sjoberg does (which is why I have it braced against the wall). No doubt completing the bench will prompt another round of reorganisation.

A simple shelf holds all of my key workbench appliances, and adds some much needed mass to the bench