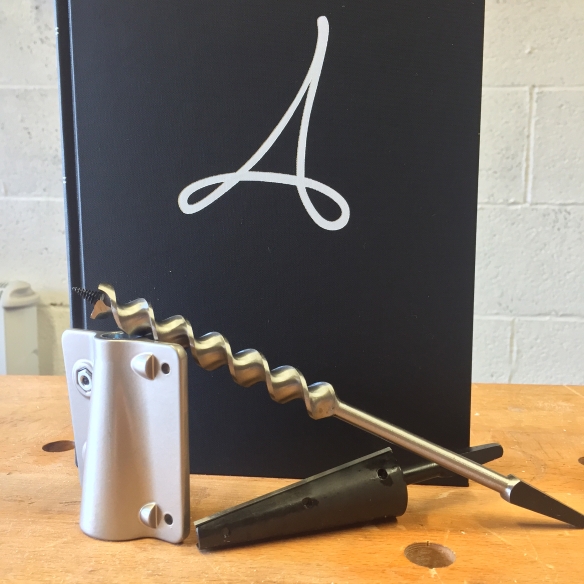

If you’re going to use hand saws then you need a pair of sturdy saw benches (or maybe three benches, if you work with very long stock). I’ve been limping along without any saw benches for a long time now, mainly because I tend to make rip cuts with an overhand rip while stock is clamped to the bench, and most of my crosscuts are narrow enough to make them at the bench hook. But with a new crosscut panel saw on order from Skelton Saws, it is time to address the chronic lack of saw benches in my workshop.

There is a wide selection of saw bench designs available, and for a long time I was tempted by Tom’s excellent design. In the end I plumbed for Chris’ saw bench design from the Anarchist’s Design Book, partly because this is a good solid saw bench that will last for years to come, but also because the staked construction offers an excellent entry point to the world of chair making (something I’ve long wanted to dip my toe into). I suppose that choosing the staked saw bench design is consistent with a summer that has been focused not just on the immediate projects on my workbench, but also on developing a core skill set that will see me through a lifetime of working wood.

For my saw benches I’m using Yellow Poplar tops and Ash for the legs – both sturdy but cost effective materials. I bought these as part of the timber run I made to Sykes Timber for the Packing Crate and School Box builds, and the saw bench materials have been sitting in the workshop acclimitising for two months prior to use.

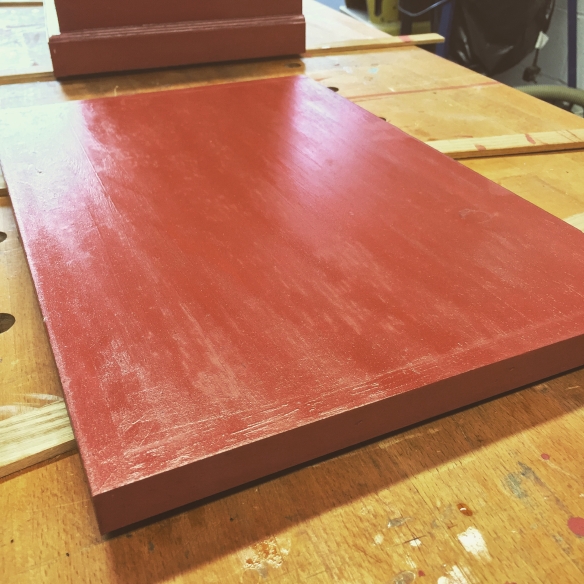

One top down, one to go.

Speaking of those core skills, the first task was to process the stock for the bench tops. I cross cut the Yellow Poplar plank so that each piece was slightly overlength, before working each top separately. On the whole this was exactly the same as dressing the stock for the School Box, and it was interesting to see how much quicker and more efficient I was at working the bench tops by hand after working on the School Box – once you have these skills locked in they stay with you.

Ripping 3″ thick Yellow Poplar by hand feels a lot like real work.

The Yellow Poplar I’d bought was in the rough, and several inches wider than I needed. I flattened one face of each piece and one reference side, before marking out the width with a panel gauge and ripping the excess width off, following which I could dress the remaining side and face. Which is all pretty standard.

Slowly emerging out of the rough

Thanks to the hefty dimensions involved in staked furniture there were a couple of moments when simply applying the lessons from The Joiner & Cabinet Maker didn’t quite work. The first was the reference edge, which at 3″ wide was significantly wider than my jointer plane. Instead of working the edge in the normal way, I treated it like a relatively narrow face, working with overlapping plane strokes until it was straight, flat, and perpendicular to the reference face. The second edge was less of an issue because I waited until the workpiece was down to thickness (2.5″) before dressing it, which meant that my jointer plane could deal with it in a single full width cut – always work smarter, not harder.

The second area where I couldn’t treat the bench top in the ordinary way was trimming the end grain – a 2.5″ thick, 7.5″ wide slab has an awful lot of end grain, and was too thick to be trimmed on the shooting board. Simply taking the jointer plane to this end grain would have likely resulted in spelching every which way, something no one would enjoy. Instead, I knifed in a good deep kerf on all four sides of the board, and chamfered down to the knife line with my low angle block plane. It was then a simple case of removing the waste between the four chamfers with the block plane until the end grain was entirely flat and the chamfers had disappeared.

Here you can see the knife kerf, and the chamfers preventing spelching. Just remove the hump between the chamfers and keep going until you hit the knife line on all four sides.

Trimming the end grain was probably the most labour intensive element of processing stock for the bench tops, and requires a really sharp blade. The end result is worth it however, as square ends are critical for laying out the leg mortices, and torn out, lumpy end grain would look very sloppy on a design which prioritises clean lines.

The end grain flattened, and square to the rest of the board

With both tops processed, I trimmed the legs to length and stickered them ready for tapering.