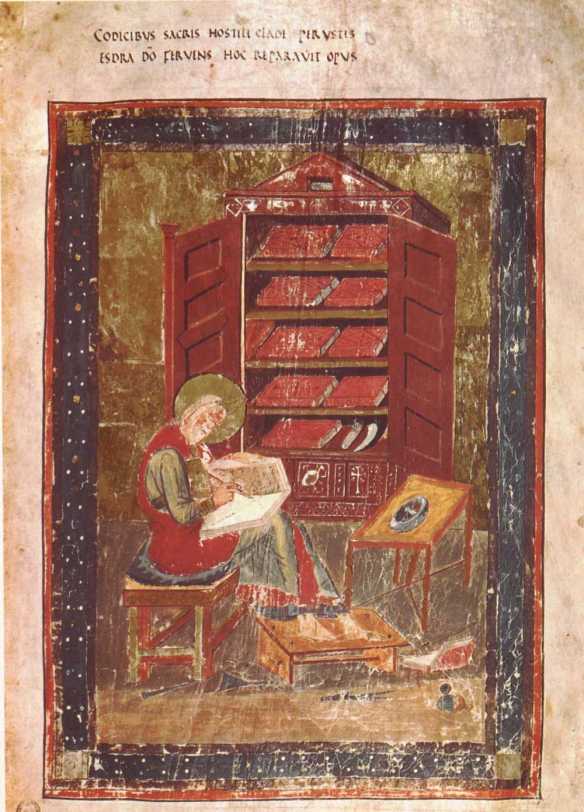

This portrait of Ezra from an 8th century bible may be one of the first illustrations of what we would recognise as a bookcase

I suppose it was inevitable that bookcases would eventually be the subject of my attention as a woodworker. I’ve always been a voracious reader and my book buying habit was only reinforced by studying history at undergraduate and graduate level, habits which were amplified by my wife’s profession (she is a lecturer in history at the University of Northampton) and appetite for reading. When Dr Moss and I moved in together, one of our first acts was to buy seven Billy bookcases to house our combined literature and history library. At that time, I was setting up my first workshop having studied lutherie at the Totnes School of Guitarmaking, and furniture building seemed like a different world to building guitars. So, a trip to IKEA and carrying seven flatpack bookcases up the torturous steps to our house it was. Six of those Billies survived two house moves and eight years of constant overloading, but their days are numbered and I now make more furniture than I do guitars. It is time to replace the Billies and to liberate the several boxes of books that have languished for years on my study floor.

Why should any of this matter? Well, because for as long as I can remember, I’ve viewed bookcases as a storage solution for the question of “where do I put all these books?” But I’ve not stopped to think about the bookcases themselves all that much. That’s how most folk think about bookcases; even the librarians in charge of historic collections tend to look at the contents of the shelves instead of the casework. Book storage is largely ignored until you don’t have enough of it.

But when you look beyond the books, and start to tease of the “why” and the “how” of book storage, things get interesting. Chris first talked to me about his idea for “The Book Book” in the autumn of 2017, and I was hooked. Not only was this a chance to replace those Billies, but also to piece together why bookcases developed into the form we now recognise. That is a path we’ve been on in earnest for a year now, and it is a fascinating opportunity to jump down many rabbit holes and to ask questions that might seem obvious, but for which no easy answers are available.

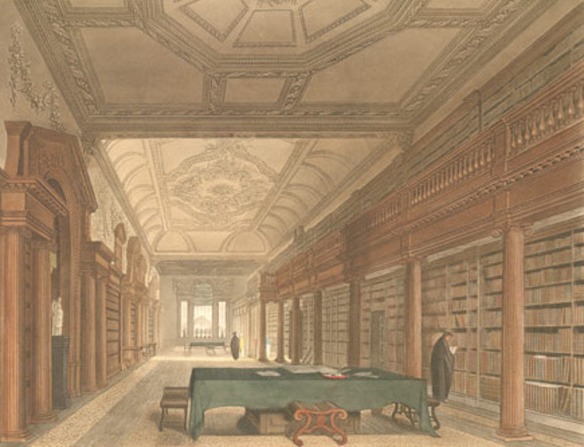

Construction of the library at Christ Church, Oxford spanned a period of 63 years

One of the few books on this subject is “The Book on the Bookcase” by Henry Petroski – a fine book, but which focuses more on the “how” than the “why”. And the “why” is where the real action is. Book technology is a recognised field of historic research, but one that is concerned more with the making and use of books rather than how book storage developed, but it can tell inadvertently tell us plenty about the factors that shaped bookcase development. Bookcases have developed to house books, so understanding why books are the sizes and shapes they are, the customs of book usage, and value and importance placed on books, all tell us something about why bookcases developed how they did.

“Oh, that’s easy” you might think. The development of the Gutenberg press encouraged standardised paper sizes which then determined shelf spacing. Well, possibly, but why those sizes and height-to-width ratios? Book storage pre-dates the printing press by hundreds of years – as soon as the first book was created, storage space was needed. And so, “The Book Book” becomes a wonderful opportunity to challenge preconceptions about book usage and production. It is a winding path from a monk fraudulently putting his name to a book in the 8th century, through court rolls, the medieval practices of producing books by scribes (both professional and amateur), the development of the printing press and early modern book production, the unchaining of libraries in the 16th century, 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys, campaign furniture, Thomas Jefferson, William Morris, to Danish minimalism and beyond. And breathe. Do you want to know what the earliest documented instance of adjustable shelving in bookcases occurred? So do we.

Lincoln College, Oxford houses striking 18th century bookcases

When woodworkers ask me what sort of book “The Book Book” will be, the closest example I can think of is “Ingenious Mechanicks.” Like that book, we will present a rigorously researched history (in this case of the development of the bookcase) alongside practical woodwork. As well as combing through texts on book technology, and scouring art history for examples of bookcases (the earliest example I can find dates from the 8th century), I’ve been researching the furniture record. In particular, historic bookcases still in use at Oxford University, some of which are over 500 years old, and the Pepys Library at Cambridge University. Historic bookcases give us key information on three key questions – what book storage was needed at the time of construction, how the bookcases were constructed, and then how they have been altered while in use due to changing needs.

We will also be building notable historic bookcases, and covering techniques and practical considerations for designing and building bookcases. All you need to know to build your own book storage; the information I wished I’d had when I stood at that IKEA checkout with my mountain of Billy bookcases eight years ago.

I’ll be blogging about the research process and the breadcrumbs we have discovered, both here and on the Lost Art Press blog. I hope you will join us on this path.